In Section 1 of its 14th Amendment, the U.S. Constitution reads in pertinent part: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Proposed by Congress in 1866 — and deemed by a procedurally-rare subsequent vote of Congress to have been validly ratified by the sufficient number of state legislatures in 1868 — the 14th Amendment is among the Constitution’s lengthiest and it touches upon a number of different topics each of which could stand alone.

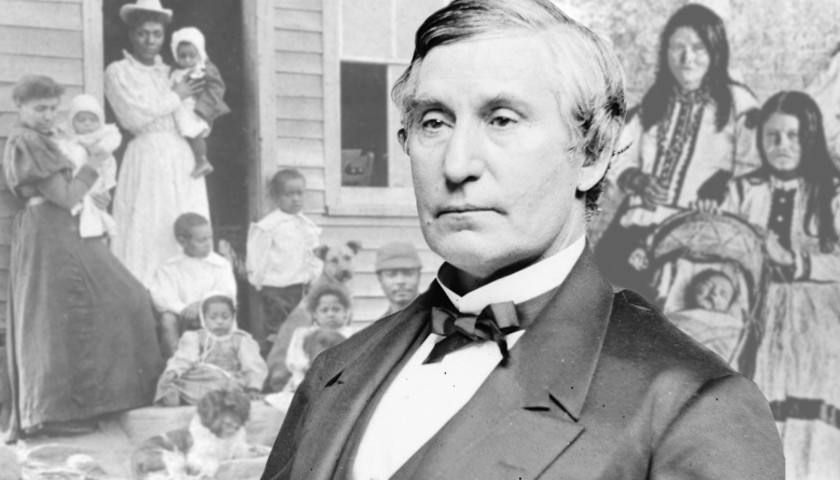

Authorship of the above-quoted words has been attributed to United States Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan. This particular provision of the 14th Amendment is generally acknowledged to overturn the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the now-infamous 1857 case of Dred Scott v. Sandford in which it had been determined that African-Americans born in the United States — to parents likewise born within the United States — could not be deemed to be American citizens.

Often overlooked by persons professing to be in-the-know about the 14th Amendment, and what it does — or does not — convey about birth citizenship are the key words “…and subject to the jurisdiction thereof…”. Those six important words must not simply be ignored — they are crucial to a proper interpretation of the 14th Amendment’s definition of U.S. citizenship and to whom such citizenship applies.

When seeking to divine the legislative intent of a federal constitutional amendment, it is wise to review the actual words of those who wrote it and voted upon it. During the original 1866 congressional debate (found on the crumbling and browned pages of The Congressional Globe) surrounding what ended up becoming the 14th Amendment, Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, had this to say about the oft-disregarded six words:

What do we [the committee reporting the clause] mean by ‘subject to the jurisdiction of the United States?’ Not owing allegiance to anybody else. That is what it means. Can you sue a Navajoe Indian in court? Are they in any sense subject to the complete jurisdiction of the United States? By no means. We make treaties with them, and therefore they are not subject to our jurisdiction. If they were, we would not make treaties with them. If we want to control the Navajoes, or any other Indians of which the Senator from Wisconsin [James Rood Doolittle] has spoken, how do we do it? Do we pass a law to control them? Are they subject to our jurisdiction in that sense?”

Trumbull, in reinforcing his point, went on to declare: “We cannot make a treaty with ourselves; it would be absurd.”

Senator Reverdy Johnson of Maryland then chimed in as to the meaning of the frequently-dismissed six words:

Now, all that this amendment provides is, that all persons born in the United States and not subject to some foreign Power — for that, no doubt, is the meaning of the committee who have brought the matter before us — shall be considered as citizens of the United States.

….

If there are to be citizens of the United States entitled everywhere to the character of citizens of the United States there should be some certain definition of what citizenship is, what has created the character of citizen as between himself and the United States, and the amendment says that citizenship may depend upon birth, and I know of no better way to give rise to citizenship than the fact of birth within the territory of the United States, born of parents who at the time were subject to the authority of the United States.”

The aforementioned Senator Howard, the Michigan Republican himself, deemed fit to add:

I think the language as it stands is sufficiently certain and exact. It is that ‘all persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.’ I concur entirely with the honorable Senator from Illinois [Lyman Trumbull] in holding that the word ‘jurisdiction,’ as here employed ought to be construed so as to imply a full and complete jurisdiction on the part of the United States, coextensive in all respects with the constitutional power of the United States, whether exercised by Congress, by the executive, or by the judicial department; that is to say, the same jurisdiction in extent and quality as applies to every citizen of the United States now.”

In the 1884 case of Elk v. Wilkins, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized the impact of “…and subject to the jurisdiction thereof…” ruling that the six-word phrase excluded from birthright American citizenship a child born on U.S. soil of Native American parents who themselves owed allegiance to the Winnebago tribe and whose son, therefore, was not “…subject to the jurisdiction…” of the United States and, ergo, not a U.S. citizen. Said the Court:

A petition alleging that the plaintiff is an Indian, and was born within the United States, and has severed his tribal relation to the Indian tribes, and fully and completely surrendered himself to the jurisdiction of the United States, and still so continues subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, and is a bona fide resident of the Nebraska and City of Omaha, does not show that he is a citizen of the United States under the Fourteenth Article of Amendment of the Constitution.”

In Title 8 (“Aliens and Nationality”) of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Section 101.3, we are further told:

A person born in the United States to a foreign diplomatic officer accredited to the United States, as a matter of international law, is not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. That person is not a United States citizen under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Such a person may be considered a lawful permanent resident at birth.”

On October 30, 2018, President Donald Trump announced his intention to issue an executive order to clarify that simply because a child happens to be born on U.S. soil does not necessarily mean that the child is a U.S. citizen solely by virtue of that location of birth.

Indeed, an entire lucrative cottage industry has sprung up to cater to foreigners who seek American citizenship for their soon-to-be-born offspring. Known colloquially as “birth tourism”, it is the practice of a pregnant woman from another country, traveling to the United States for the intended purpose of completing that pregnancy on U.S. soil. Hence, her baby — technically born in the U.S. — has long been presumed jus soli to automatically be a U.S. citizen and, consequently, entitled to numerous benefits of American citizenship.

President Trump’s declared efforts would not be the first attempt to elucidate the 28 words of the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause.

In 1952, Congress passed — over President Harry Truman’s veto — the Immigration and Nationality Act (Public Law No. 82-414) by a vote of 278 yeas and 113 nays in the U.S. House of Representatives and by a vote of 57 yeas and 26 nays in the U.S. Senate. In that statute, it was established that a baby born on U.S. soil to, for example, an accredited diplomat is not an American citizen.

In its Section 202, Pub. L. No. 82-414 reads in relevant portion: “(3) an alien born in the United States shall be considered as having been born in the country of which he is a citizen or subject….”

The alien may, of course, later apply for lawful permanent resident status or even petition to become a U.S. citizen via the naturalization process. But, as noted in Pub. L. No. 82-414, he or she is not a U.S. citizen merely by having been born on American soil.

Despite such unambiguous pronouncements from the legislative branch as well as from the judicial branch, the executive branch of the federal government has frequently misrecognized persons born on U.S. soil to non-U.S. citizen parents to nevertheless be birthright Americans. Given this misconstruction by the executive branch, the issuance by President Trump of a clarifying executive order would appear a proper remedy.

– – –

With his decade of work (1982-1992) to gain the 27th Amendment’s incorporation into the U.S. Constitution, Gregory Watson of Texas is an internationally-recognized authority on the process by which the federal Constitution is amended.

[…] for the Tennessee Star, constitutional amendments expert Gregory Watson cites the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as a […]

the 1952 immigration act is clear in the definitions; State is; Puerta Rico, Guam, Alaska, Hawaii… 1959 Hawaii and Alaska become States of the Union. That year the United States lost two States and the United States of America gained two States. So a US citizen could only be a citizen of D.C. or the islands. That’s a fact Jack. See also pub-law 86-624 and 86-70. Omnibus act of Alaska and Hawaii

[…] for the Tennessee Star, constitutional amendments expert Gregory Watson cites the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as […]

[…] for the Tennessee Star, constitutional amendments expert Gregory Watson cites the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as […]

[…] for the Tennessee Star, constitutional amendments expert Gregory Watson cites the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as […]

[…] for the Tennessee Star, constitutional amendments expert Gregory Watson cites the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act as […]

[…] Oct. 30, President Trump announced his intention to issue an executive order to clarify that simply because a child happens to be born […]