Early on in Ma Jian’s new novel the main character has a vision: I saw elderly men and women smashing rocks against the ground under the steely gaze of teenage Red Guards. Among the sweat-drenched faces caked in dust, I saw my father looking up at me.

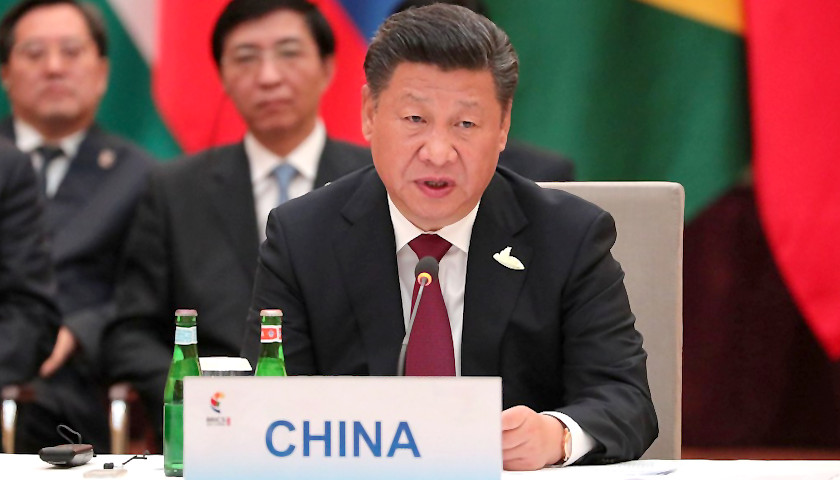

There are many anguished recollections in the book but this one carries a special poignancy. It is central to a story that shows how the personal (with a hint of parricidal guilt) and the social (an ancestral culture) were torn to pieces in a murderous, ideological frenzy in the service of Mao Zedong’s “struggle against all incorrect ideas and actions.” Under President for life Xi Jinping, that struggle continues today in China, only with much better technology.

“China Dream” – the novel takes its title from Xi Jinping’s “national rejuvenation” program of the same name – traces the progressive psychic disintegration of Ma Daode, director of the newly created China Dream Bureau in the provincial city of Ziyang. It is a work of fiction, but could equally be read for what it is: a scathing report on the political and cultural pathologies that are plaguing present-day China. Boozy, potbellied, corrupt, beset by bureaucratic rivals, a resentful wife and at least a dozen mistresses, Daode’s mission is to promote Xi Jinping’s program — equal parts nationalism and Maoist-lite propaganda — to convince the Chinese that they are being led, after decades of humiliations, to rightful restoration of their place as one of the world’s great nations.

But there’s a problem. Daode, like the nation itself, hasn’t resolved the repressed memories that flow out of the manifold horrors of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) including, according to some reports, beheadings and cannibalism. Try as he will, the memories and the heavy guilt he carries flood back at the most inopportune times – during mind-numbing party meetings, planning local pageants in celebration of the China Dream, or while exchanging off-color jokes and racy text messages with his mistresses. The guilty memories of the vicious factional fighting he engaged in as an adolescent are now triggered simply at the sight of former classmates as he is shuttled around promoting the China Dream. Worst of all are the vivid memories of his parents – unjustly victimized by marauding Maoist persecutors and interred in a mass burial ground. And here he carries the deepest burden of guilt.

Like other party members, Daode’s cynicism and ability to mouth lies about a despotic regime appear boundless. In his official capacity, his job is to promote “the great China dream that will replace all private dreams.” His worry is not that his project is an affront to human dignity and freedom of conscience, but only that doing too good of a job of it might make his cushy Communist Party position redundant.

Like other party members, Daode’s cynicism and ability to mouth lies about a despotic regime appear boundless. In his official capacity, his job is to promote “the great China dream that will replace all private dreams.” His worry is not that his project is an affront to human dignity and freedom of conscience, but only that doing too good of a job of it might make his cushy Communist Party position redundant.

Jian’s novel is set in present-day China – troubling enough – but Daode has come up with a harebrained scheme that hints at a dystopian near future. He plans to insert a neural implant, or brain chip, into the heads of fellow citizens in order to fully impregnate their minds with Xi Jinping Thought and wash away all private remembrances. (“just one click of a button and government directives will be transmitted wirelessly into the brains of every Party member in the country.”) This is s 21st-century twist on brainwashing (a term coined in the 1950s by the Chinese Communists) and practiced during the Cultural Revolution and beyond.

Unlike George Orwell, who had to invent a future where Big Brother recorded everything once considered private and banished inconvenient history into the Memory Hole, Jian in his novel didn’t have to make much of a leap into the future. Not with mass surveillance, AI-powered facial recognition, mandatory DNA testing of ethnic minorities with help from the corporate America, social credit scores, and burgeoning detention camps the stuff of daily China news reports. Unlike Aldous Huxley in “Brave New World,” Jian didn’t have to invent a drug like soma to zombie-fy the populace. The novelist shows how the pervasive media propaganda of the Communist regime and the monstrous lies it tells infantilizes and stupefies a worshipful populace.

Xi Ping’s world-class surveillance state plays a central role in “China Dream.” While fielding a text from Lei Wei, his first and oldest mistress who has a penchant for pornographic emojis, Daode hears his official phone (he keeps another two at the ready) buzzing from an Internet censor who asks if he should delete an online comment that “seems like a dig at corrupt officials.” Of course it should be deleted. And everything, in Daode’s world, works symbiotically with the ministries of propaganda and security.

Party members in Jian’s story must also deal with the inevitable paranoia engendered by a system that consumes its own. After exchanging flirtatious glances with one of his younger mistresses at a meeting, Daode muses that young people in today’s China have no idea how dangerous politics can be. His mind involuntarily shoots back to his time in a village during the Cultural Revolution when guards stormed into a classroom to arrest a 12-year-old who had scraped a sliver of plaster off of a Mao statue to use as a setting agent for bean curd. The director breaks into a snap sweat. “It suddenly occurs to Mao Daode that when he fits the China Dream Device into his brain, all these memories that keep popping up without warning will be forwarded straight to the Ministry of Supervision.” If my past keeps bursting through like this, Daode thinks to himself. I will fall apart.

Try as he might, he cannot extinguish memories of the internecine slaughter – mobs of adolescents fighting with fists, bricks, knives and machine guns and the piles of rotting corpses left in the open. The Cultural Revolution has moved back into his head. Imprudently, he visits a brothel (which he learned about through the party’s anti-pornography program) done up in kitschy Maoist décor, karaoke screens and revolutionary songs playing incessantly, and where the prostitutes are dressed as Red Guards. He asks one of the girls at the nightclub if she’s heard of the Cultural Revolution. “Not really – what was it exactly?” she answers. As the night progresses, the bottles empty, more texts fill his phone, the inevitably the images pour into his head. This time from the Great Leap Forward (1958-62) and resulting famine that claimed an estimated 45 million lives:

My family and I lived in Yaobang for only six months during the Great Famine, and I was just eight years old. But some memories of that time are still vivid. I remember seeing villagers peeling the bark from trees and eating it to fend off starvation. And I remember seeing a woman sitting on her porch, stone dead, her hands still gripping an empty bowl.

Not everyone in Jian’s novel is as thoroughly venal, corrupt and cynical as the local Communist party officials Daode contends with daily (the house where he and his wife Juan live is stuffed with gifts brought as bribes for jobs and other favors; gold bars and rolls of 100-yuan notes are preferred). Daode is sent to Yaobang, a farming community not far from Ziyang that, the government has directed, must give way to a planned industrial park with promises of hi-tech employment. But the farmers and other villagers (some whose relatives were put in work camps as “rich peasants” during the Cultural Revolution) aren’t having any of it. They organize a crude militia to make a stand, to protect their ancestral homes, and shout curses and threats at Daode. The villagers fear a future life of wandering from one low paid factory job to another. But they cannot withstand the might of the party directive – with its bulldozers and squadrons of armed police and informants in their own ranks. As they are hauled off, a Molotov cocktail explodes and burns a banner: Make The China Dream Come True And Fight To The Bitter End To Defend Our Homeland

So desperate is Daode to clear his head – he also bears the physical scars from a knife attack during the Cultural Revolution – that he seeks the practical help, if not the spiritual consolation, of a Qigong healer named Master Wang. This charlatan prescribes a noxious potion called Old Lady’s Dream Broth of Amnesia which, of course, will cost Daode plenty. He is only too glad to pay up and as best he can assemble the stomach-churning ingredients for Wang’s recipe, mixes it up, and carries it with him everywhere in a Coca-Cola bottle. This, incidentally, he plans to turn into a fortune under the China Dream Soup brand. In the end, Daode wanders like a ghost through the streets with a cardboard placard strung around his neck announcing himself as the director of the China Dream Bureau. He is mocked and abandoned by all – the wife, the party members, the many mistresses, street food vendors – and staggers in an uncomprehending fog. He looks down at the sign hanging around his neck and asks himself, But which Ma Daode am I?

Or, is he really asking, Which China am I living in? The answer seems all too clear. It’s Xi Jinping’s China, and Daode is living in it. He will be who the state says he will be.

In the foreword to his novel, Ma Jian described Xi Jinping’s China Dream as “another beautiful lie concocted by the state to remove dark memories from Chinese brains and replace them with happy thoughts.” Decades of Community Party lies and indoctrination, he writes, along with nationalism and consumerism, have left the Chinese people “so numb and confused, they have lost the ability to tell fact from fiction.”

In Jian’s vision, Director Ma Daode of the China Dream Bureau, stands for them all. How long will China go on in this fog of lies, he seems to ask, before the nation itself begins to disintegrate?

– – –

John Couretas is Director of Communications, responsible for print and online communications at the Acton Institute. He has more than 20 years of experience in news and publishing fields. He has worked as a staff writer on newspapers and magazines, covering business and government. John holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in the Humanities from Michigan State University and a Master of Science Degree in Journalism from Northwestern University.

Photo”Xi Jinping” by Kremlin.ru. CC BY 4.0.