by Tate Fegley

There is a case – Timbs v. Indiana – currently before the United States Supreme Court regarding civil asset forfeiture and whether the excessive fines clause of the 8th Amendment also applies to the states due to the 14th Amendment’s incorporation clause.

The petitioner is Tyson Timbs, who became addicted to the opioid hydrocodone after having received a prescription for his foot pain. After his prescription had run out, he bought it from a dealer. After his dealer had run out, he was persuaded to try heroin as a substitute and became addicted. He eventually overcame his addiction but relapsed around the time of his father’s death.

Timbs received $73,000 from his father’s life insurance policy and used $42,000 of it to buy a 2012 Land Rover. Wanting to make money to fund his habit, he was convinced by a confidential informant to deal heroin. He made two deals with undercover narcotics agents (each deal for two grams) and, on his way to the third deal, was pulled over and arrested. His Land Rover was seized on the spot.

Timbs was charged with two counts of dealing in a controlled substance and one count of conspiracy to commit theft. He pleaded guilty to the latter charge and to one of the two counts of the former. The maximum fine that could be imposed for his criminal offenses is $10,000. The trial court found that the seizure of a vehicle worth over four times the maximum fine violates the 8th Amendment’s prohibition against excessive fines. While a divided appeals court affirmed the decision, the Indiana Supreme Court reversed, arguing that there is no precedent establishing that the excessive fines clause of the 8th Amendment applies to the states. The US Supreme Court granted review and heard oral arguments on November 28, 2018.

In the transcript of the oral arguments, it seems that a majority of the Court was skeptical of the idea that the excessive fines clause had not been incorporated to the states. Justice Gorsuch, for example, challenged Indiana’s solicitor general Thomas Fisher, saying “most of these incorporation cases took place in the 1940s. And here we are in 2018 still litigating incorporation of the Bill of Rights. Really? Come on, General.” In all likelihood, the Court will decide the question before it — does the excessive fines clause apply to the states? — in the affirmative.

SCOTUS Isn’t Likely to Define “Excessive Fines”

However, there’s the bigger question: is this case momentous in terms of limiting the abuse of civil asset forfeiture? Probably not. There are a number of reasons why.

For one thing, the Court’s decision will not speak to the question of what constitutes an excessive fine in regards to civil asset forfeiture. In Austin v. United States (1993) the Court held that civil asset forfeiture can be considered a punishment of the owner of the property — not just a case against the property being seized – but refused to provide a test to determine what constitutes “excessive.” Indeed, not many cases have come before the Court to adjudicate what the prohibition against excessive fines means, even outside of civil asset forfeiture. In United States v. Bajakajian (1998) , we were at least given an example of what type of fine the Court considers “grossly disproportional to the gravity of the defendant’s offense” when Mr. Bajakajian’s $357,144 in cash was seized when he failed to report to customs officials that he was carrying more than $10,000 as he was leaving the country to pay debts. But the Court will likely not comment on whether the seizure of a $42,000 truck is excessive for a crime with a maximum penalty of $10,000.

Second, the value of the property seized in most cases of civil asset forfeiture will likely not be considered excessive by courts. The Institute for Justice (one of the litigators in this case), collected property-level forfeiture data for 10 states in 2012. The median value of seized property ranged from $451 in Minnesota to $2,048 in Utah. Similarly, the ACLU of Pennsylvania found in its analysis of cash forfeitures in Philadelphia between 2011 and 2013 that half of the cases involved less than $192. In the majority of cases, property owners choose not to even challenge the forfeiture, one of the primary reasons undoubtedly being that the legal costs of doing so are greater than the value of the property.

It’s at the State Level Where Real Reform Is Possible

But perhaps the biggest reason the Court’s decision will make no short term difference in curbing civil asset forfeiture abuse (which is shockingly something almost no one is mentioning regarding this case) is that the vast majority of state constitutions already prohibit excessive fines! Timbs v. Indiana should not have come before the US Supreme Court for the simple reason that there is already a clause in the Indiana state constitution prohibiting excessive fines. Why didn’t the Indiana Supreme Court look to its own state constitution to confirm that, regardless of whether the 8th Amendment’s excessive fines clause is incorporated to the states, Tyson Timbs was protected? The only way this case will have any impact on civil asset forfeiture is first by confirming that the excessive fines clause is incorporated to the states and then by the US Supreme Court, in future cases that come before it, defining “excessive” in a stricter way than state courts currently do. But even then it will only apply in the most egregious of cases.

For those in favor of civil asset forfeiture reform, what ought to receive more attention are efforts at the state and local levels, such as the legislation passed by New Mexico, Arizona and Nebraska, or the bill currently under consideration by North Dakota. These reforms typically require that a criminal conviction be obtained before any forfeiture takes place, and that the proceeds from what is seized go to a general or school fund rather than to supplement the police department’s budget. One crucial element of reform, however, that has not been implemented by all states passing reforms is closing the federal equitable sharing loophole by which police departments circumvent state law. Making these changes is up to the states; it will not come about through legislation or litigation at the federal level.

– – –

Tate Fegley is a 2018 Mises Institute Fellow, and winner of the 2018 Grant Aldrich Prize for Best Graduate Student Paper at the Austrian Economics Research Conference. He is currently a graduate student at George Mason University.

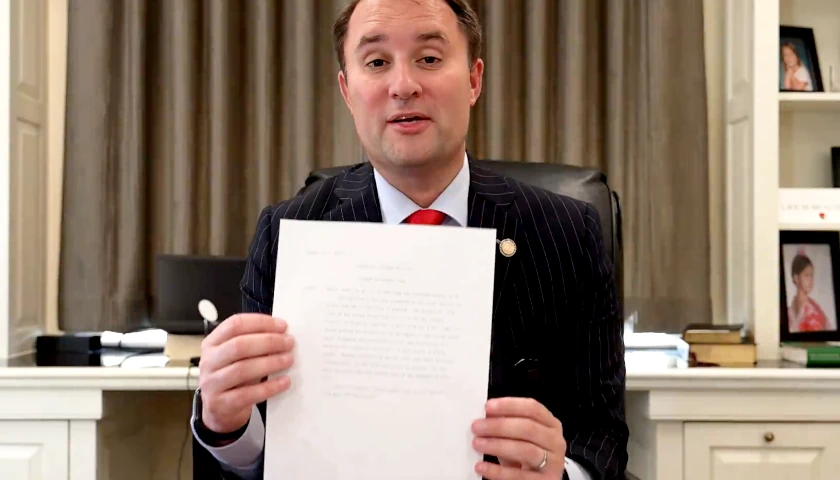

Photo “Tyson Timbs” by Institute for Justice. CC BY 4.0.