This is the thirteenth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The Sixth Amendment, like the Fourth Amendment and the Fifth Amendment, primarily focuses on the protection of individual liberties against the police powers of the state:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have previously been ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

A good way to remember the Sixth Amendment is that it guarantees six very specific rights to every citizen:

(1) If you ever accused of a crime, and prosecuted criminally, you have the right to a speedy and public trial

(2) You have a right to be tried by an impartial jury of your peers.

(3) You have the right to know what crime you’re being charged with and why. In the parlance of the day used in the amendment, you had the right “to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation.”

(4) You have the right to see, hear, and question–“to be confronted with” the witnesses against you.

(5) You have the right to bring your own witnesses to be heard on your behalf at trial.

(6) You have the right to be represented by a lawyer as “counsel for your defence.”

These rights seem obvious and common place to us today.

They were all well established in America at the time of the American Revolution, but had, at times, not been granted during the Colonial period.

Indeed, there was a period of time during the 17th Century when Colonial British America, as it was called at the time, suffered from the same lack of these rights, as did the mother country of England.

The abuses of these long-standing rights were perhaps most severe during the period of the reign of King Charles I from 1629 to 1640 when the king refused to call Parliament in to session.

It was during this decade that the infamous “Star Chamber” trials were conducted in secret and in French. The accused brought before these special tribunals, established for the purpose of prosecuting the political enemies of the king, did not have any of the rights now granted to every American citizen as part of the Sixth Amendment.

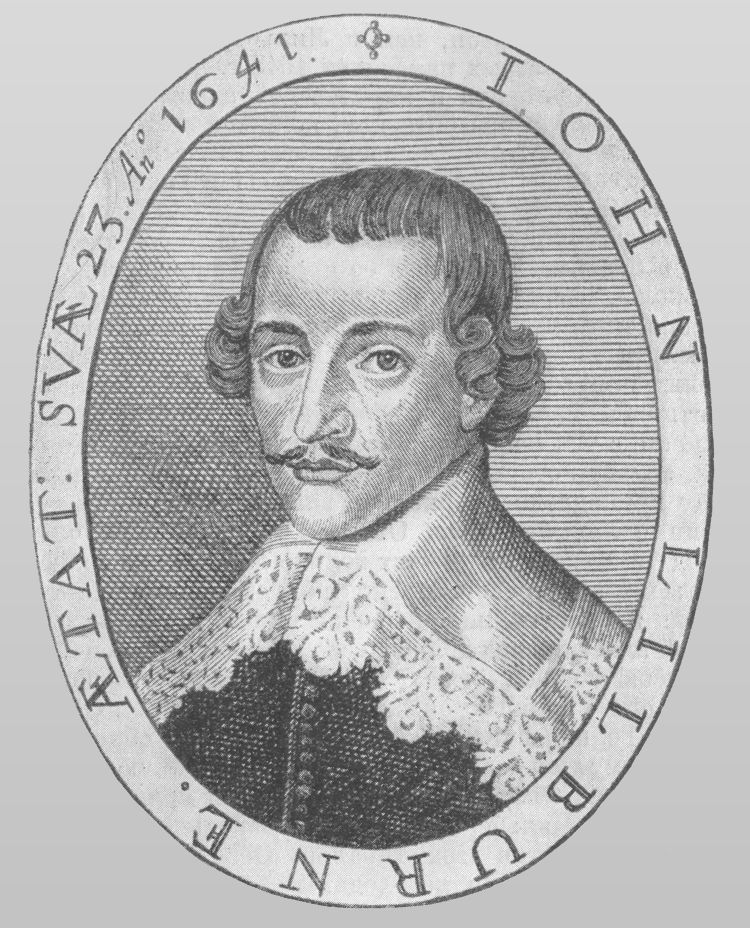

John Lilburne, an early hero of popular resistance to the King’s tyranny and a distant relative of our own Thomas Jefferson, was perhaps one of the most noteworthy Englishmen to be convicted and imprisoned by a Star Chamber trial.

John Lilburne, an early hero of popular resistance to the King’s tyranny and a distant relative of our own Thomas Jefferson, was perhaps one of the most noteworthy Englishmen to be convicted and imprisoned by a Star Chamber trial.

“The tall and charismatic Lilburne entered the public eye in 1638, at the height of Charles I’s era of personal rule. Only twenty-four at the time, Lilburne was arrested and tried for smuggling “unlicensed” Christian books from Holland to England,” Michael Patrick wrote of Lilburne in his 2012 book, Covenant of Liberty: The Ideological Origins of The Tea Party Movement:

He was not tried in a common law court by a jury of twelve peers, where he would have been granted the right to his own legal counsel. Instead, his case was brought before the Star Chamber. Previously, this special court had been used for expedited hearings on matters involving important figures who might have influenced the outcome of common trials. Charles transformed the Star Chamger into his personal vehicle for eliminating enemies and forcing compliance with established regulations limiting dissent. By the time Lilburne was brought in chains before it, the Star Chamber had become the symbol of the abuse of power that characterized Charles’s rule.

“Addressing Lilburne in the customary “Law French,” of the Star Chamber, the judges demanded to hear his plea,” Leahy wrote:

Lilburne refused to plead until he heard the charges in English. Angered by his defiance, the court ordered him to be stripped of his shirt and tied to an oxcart, behind which he walked for two miles. Crowds gathered to watch was he was lashed more than two hundred times with a three-tailed whip. When he arrived at his destination–the front yard of Westminster–he was untied from the cart and placed into a pillory.

“Defying his captors, Lilburne removed the banned religious books he had hidden in his pockets, threw them into the crowd, and loudly proclaimed that his punishment was a violation of his rights as an Englishman. His captors quickly gagged him, but he had won the hearts of his countrymen and became a symbol of resistance to the arbitrary power of the king,” Leahy noted:

The price for this demonstration of courage was high. He remained in prison under severe conditions for more than two years, released only when Charles I was compelled to call Parliament into session to finance his “Bishops’ Wars” against Scotland. He emerged severely malnourished. He no longer could use two of his fingers, casualties of two years of wrist chains.

More than three hundred years later, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black paid tribute to Lilburne, “and cited his refusal to enter a plea to unknown charges as the basis for the Fifth Amendment–the protection against self-incrimination.”

In 1959, Justice Black cited Lilburne’s 17th century ordeal in England when he wrote his dissent in a case called Barenblatt v. United States. The Founding Fathers, he wrote, “believed that punishment was too serious a matter to be entrusted to any group other than an independent judiciary and a jury of twelve men acting on previously passed, unambiguous laws, with all the procedural safeguards they put in the Constitution as essential to a fair trial–safeguards which included the right to counsel, compulsory process for witnesses, specific indictments, confrontation of accusers, as well as protection against self-incrimination, double jeopardy and cruel and unusual punishment–in short, due process of law.”

They believed this because not long before worthy men had been deprived of their liberties, and indeed thir lives, through parliamentary trials without these safeguards. The memory of one John Lilburne–banished and disgraced by a parliamentary committee if he returned to his country–was particularly vivid when our Constitution was written. His attack on trials by such committees and his warning that “what is done unto any one, may be done unto every one,” were part of the history of the times which moved those who wrote our Constitution to determine that no such occur over here.

“It is the protection from arbitrary punishments through the right to a judicial trial with all these safeguards which over the years has distinguished America from lands where drumhead courts and other similar ‘tribunals’ deprive the weak and the unorthodox of life, liberty and property without due process of law,” Black concluded.

In 1966, “Lilburne’s Star Chamber trial was also cited as a significant historical precedent in the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in the landmark case Miranda v. Arizona.”

Chief Justice Warren wrote specifically of that trial’s influence on the Founding Fathers when they wrote the Fifth Amendment, but its due process protections apply to the Sixth Amendment as well.

“We sometimes forget how long it has taken to establish the privilege against self-incrimination, the sources from which it came, and the fervor with which it was defended. Its roots go back into ancient times,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in his majority opinion:

The critical historical event shedding light on its origins and evolution was the trial of one John Lilburn, a vocal anti-Stuart Leveller, who was made to take the Star Chamber Oath in 1637. The oath would have bound him to answer to all questions posed to him on any subject. He resisted the oath and declaimed the proceedings, stating:

“Another fundamental right I then contended for was that no man’s conscience ought to be racked by oaths imposed to answer to questions concerning himself in matters criminal, or pretended to be so.”

On account of the Lilburn Trial, Parliament abolished the inquisitorial Court of Star Chamber and went further in giving him generous reparation. The lofty principles to which Lilburn had appealed during his trial gained popular acceptance in England. These sentiments worked their way over to the Colonies, and were implanted after great struggle into the Bill of Rights. Those who framed our Constitution and the Bill of Rights were ever aware of subtle encroachments on individual liberty. They knew that “illegitimate and unconstitutional practices get their first footing . . . by silent approaches and slight deviations from legal modes of procedure.” Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616, 635 (1886).

“The privilege was elevated to constitutional status, and has always been “as broad as the mischief against which it seeks to guard.” Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U. S. 547, 562 (1892). We cannot depart from this noble heritage, “Warren concluded.

It is hard to overemphasize the English roots of American liberty, or the significance of Lilburne’s part of in that influence.

As it turns out, Lilburne was close friends with another young man from England who was undergoing his own trials after having arrived in America just a few years before Lilburne’s Star Chamber trial. His name was Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island who literally escaped from the Massachusetts Bay Colony with a death sentence hanging over his head because his ideas on religion differed with the founders of that colony.

As we mentioned in our earlier chapter in the First Amendment, it was Roger Williams’ ideas about freedom of religion that ultimately prevailed a century and a half later when the American republic was founded, not the early leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who had a restrictive idea about how the Christian God should be worshiped and used the power of the state to enforce those ideas on others for some time.