This is the second of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

Today’s high school students may yawn when they hear teachers describe what a world-changing document the United States Constitution was when it was ratified in 1788 and a new government was formed a year later in 1789.

But a deeper look behind the scenes reveals the three dramatic innovations the Founding Fathers introduced in just 4,400 words that changed the course of history for the better over the next 228 years, not just in the United States of America, but around the word:

- A Single Written Agreement Was Now the Highest Authority for “The Rule of Law” in America

- Federalism

- The Separation of Powers

1. A Single Written Agreement Was Now the Highest Authority for “The Rule of Law” in America.

Two-thirds of the four million residents of the United States in 1789 (67 percent) were of British ancestry. Another 14 percent were from other parts of Europe. Nineteen percent (750,000) were from Africa, the vast majority of whom (700,000) were slaves, although a small number (50,000) were free. (We’ll have more on this later in another article in our Constitution Series.)

All of the thirteen original states who ratified the United States Constitution were former British colonies.

As a consequence, the government of the new United States was based on what the British called “the rule of law” — the idea that the country was governed by laws that applied to everyone, not by the arbitrary decision of one or a select group of leaders. “The rule of law” is one element that distinguishes both a republic and a constitutional monarchy from a dictatorship, an absolute monarchy, or a pure democracy.

Great Britain during the era of the Founding Fathers had a population of fourteen million, and consisted of three kingdoms on the island of Britain–England, Wales, and Scotland-united under a single government whose head of state was the king and whose laws were established by the elected Parliament, and a fourth kingdom-Ireland- on the island of Ireland that was a “client state” of the kingdom of England. By 1801, all four kingdoms would be united under one country, known as The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Great Britain had a long tradition of respect for “the rule of law,” dating back more than nine hundred years before the American Constitution–thirty generations–to the time of the Anglo-Saxon King Alfred the Great, who created not only the country of England by uniting the ancient lands of Wessex, Anglia, Mercia, and Northumberland, but also put together the first codification of English law in the “Doom Book.” (The final unification of England was accomplished by Alfred’s grandson, King Aethelstan, around 927 A.D.)

The first eight decades of the settlement Colonial British North America took place as the mother country, Great Britain, underwent its own dramatic transformation from a nation that was on the verge of becoming an absolute monarchy to one that was firmly established as a constitutional monarchy.

In 1607, when the first British settlement in North America was established in Jamestown,Virginia, Great Britain was ruled by King James I, who conducted himself as an absolute monarch and considered Parliament–the country’s elected legislative body whose tradition stretched back to the thirteenth century and beyond–as an annoyance to largely be ignored.

By 1689, when local residents of the colony of Massachusetts successfully revolted against a tyrannical governor put in place earlier by King James II, William & Mary had assumed the throne of Great Britain as constitutional monarchs who agreed to Parliamentary supremacy.

British subjects living in the mother country celebrated this Glorious Revolution–the political uprising that began in 1688 and placed William & Mary on the throne in 1689–as a restoration and advancement of the traditional British concept of “the rule of law.”

The new Parliament elected after the Glorious Revolution passed a new law–the Bill of Rights of 1689 (often called the English Bill of Rights, not to be confused with our own Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, all of which were ratified by 1791.)–that defined the terms of this new constitutional monarchy, and protected the individual liberties of British subjects wherever they lived in the world. The agreement was hailed on both sides of the Atlantic.

British subjects living in Colonial British North America–which by this time had a population of 250,000–celebrated the ascendancy of a constitutional monarchy as well.

John Locke, an influential English political philosopher whose ideas were central to rise of a constitutional monarchy and whose writings profoundly influenced the thinking of many of the Founding Fathers, summed up the concept of “the rule of law” that held sway in the minds of British subjects on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean at the time.

“Freedom is constrained by laws in both the state of nature and political society,” Locke wrote in a book called Two Treatises of Government, first published in 1689.

“Freedom of nature is to be under no other restraint but the law of nature. Freedom of people under government is to be under no restraint apart from standing rules to live by that are common to everyone in the society and made by the lawmaking power established in it,” he said.

“Persons have a right or liberty to (1) follow their own will in all things that the law has not prohibited and (2) not be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, and arbitrary wills of others,” Locke concluded.

Locke’s ideas made a lot of sense to the Founding Fathers, all of whom were born well after those words were written (the oldest Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin, was born in 1706, more than 17 years after the Glorious Revolution) but began their intellectual journeys fully on board with the British concept of a constitutional monarchy.

Had the mother country adhered to those principles, there would have been no need for an American Revolution.

But, as it turned out, Parliament and King George III began to treat British subjects in British North America differently than it treated British subjects living in Great Britain.

Great Britain (now the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) has never had a single document that defines its Constitution. In fact, until the ratification of the American Constitution in 1789, no country in the history of the world ever had a single document that served as its highest authority for “the rule of law.”

A famous English legal scholar by the name of A.V. Dicey wrote a book in the late 19th century in which he argued that England (and by extension Great Britain and now the United Kingdom) has, in fact had a Constitution for centuries, but it is not found in a single document. Instead, it is comprised of the combination of laws passed by Parliament, the common law (the collective judicial decisions of the courts over hundreds of years), “parliamentary conventions,” such as the one that enacted the reforms of the Glorious Revolution, and “works of authority,” such as the document signed in 1215 by King John and the barons of England known as The Magna Carta.

Dicey is probably correct in that assertion, but the fluid nature of the “English Constitution,” and the ability of Parliament to pass laws that changed what it said without giving proper consideration to the views of British subjects living in British North America was the ticking time bomb just waiting to explode during the second half of the 18th century.

And explode it did.

In 1765 Parliament passed the Quartering Act, which forced colonists to provide lodging to British soldiers living among them, and the Stamp Act, which placed an unwelcome tax on all newspapers, legal documents, and other printed documents in the colonies.

The colonists, with good reason, believed that these laws completely disregarded their rights as British subjects.

Then in 1767, Parliament passed even more onerous laws, known collectively as the Townshend Acts, which imposed more unwelcome taxes on the colonists, including the now infamous tax on tea.

In late 1767, a series of articles entitled “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” began to appear in publications throughout the thirteen colonies. Penned by John Dickinson, who two decades later would serve as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, these essays presented a compelling case that the imposition of taxes on the colonies by Parliament without their consent was unconstitutional–defining the English constitution as the new agreements about governance in Great Britain arising from the Glorious Revolution almost eight decades earlier. That sentiment was widely shared in the colonies.

The usurpations of the liberties of the colonists by Parliament kept piling up.

“With a good deal of surprise I have observed that little notice has been taken of an act of Parliament, as injurious in its principle to the liberties of these colonies as the Stamp Act was: I mean the act for suspending the legislation of New York,” Dickinson wrote in one of his letters.

“The assembly of that government complied with a former act of Parliament, requiring certain provisions to be made for the troops in America, in every particular, I think, except the articles of salt, pepper, and vinegar,” he noted.

The suspension of New York’s legislature, Dickinson wrote, “is a parliamentary assertion of the supreme authority of the British legislature over these colonies in the point of taxation; and it is intended to compel New York into a submission to that authority.”

“It seems therefore to me as much a violation of the liberty of the people of that province, and consequently of all these colonies, as if the Parliament had sent a number of regiments to be quartered upon them, till they should comply,” the future delegate to the Constitutional Convention concluded.

When Parliament passed The Tea Act of 1773, which removed the British East India Company’s export tax for shipping tea to British America, but left the tax on tea imported to British North America intact, the call to arms, “No Taxation Without Representation” reverberated throughout the colonies.

Fourteen years later, after the American Revolution had been fought and won, and the Articles of Confederation had clearly failed, the delegates who gathered at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in May of 1787 knew they had to create a single, lasting, definitive document that every colony could agree to that would be the highest authority for what “the rule of law” meant in America.

And that is exactly what they produced in the Constitution that was ratified and created the United States of America in 1789.

That highest authority could be changed, but those changes–called amendments–required a much more elaborate and participative process than the mere enacting of a single statute by the new country’s legislative body.

As for the document that emerged, it set the standard for two key concepts of governance that, while present in a few other smaller countries at the time, had never been fully developed in the creation of a major nation: federalism and the separation of powers.

Once the rest of the world saw it, they took notice. Soon, other countries began to follow the example of the United States.

Not all of the governments established by those single document constitutions have fared as well as our own.

The French Constitution of 1791, ratified just two years after the formation of the new government of the United States, established a constitutional monarchy to replace the absolute monarchy of the ill-fated King Louis XVI. That agreement barely lasted a year, and was replaced by the French Constitution of 1793, which established the first of five French republics, each with its own constitution. The current French Constitution of 1958 established the Fifth French Republic.

The Polish Constitution of 1791, which established a constitutional monarchy, also lasted less then two years.

In 1814, Norway had better luck with the Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway, which established a constitutional monarchy that continues to this day.

Now, in 2017, more than one hundred countries have a single written document that serves as their constitution. However, in many of those countries the document has little impact, since they lack the same tradition of and respect for “the rule of law” found in the United States and Great Britain.

Tomorrow, in the second of this week’s articles on the three things that make the United States Constitution unique in the history of the world, we’ll talk about (2) Federalism, then on Wednesday in our third article this week we’ll look at (3) The Separation of Powers.

Three Things That Make the United States Constitution Unique in World History

Part Two: Federalism

This is the second part of the second of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

Federalism is a foundational concept framed in the Constitution of the United States which defines the relationship between the national government and each of the state governments that comprise our republic (thirteen such state governments in 1789, fifty now in 2017).

Both entities–the national government and each state government–remain sovereign, while the powers of governance and responsibilities to the citizenry are balanced between the two. Federalism, along with The Separation of Powers within the national government (which we will discuss in tomorrow’s article) are the two foundational concepts of the Constitution that protect the freedoms and liberties guaranteed to individual citizens.

“In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each subdivided among distinct and separate departments,” James Madison, probably, or Alexander Hamilton, possibly, wrote of “the federal system of America” in Federalist Paper #51, one of the famous series of essays written after the Constitutional Convention designed to persuade the thirteen separate states to ratify it.

“Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself,” they concluded.

While revising the Articles of Confederation, delegates to the Constitutional Convention finally confronted the proper role of the states, the constitutional branch of government closest to the people being governed.

Though the document that emerged from the convention increased the powers of the national government, which were virtually non-existent under the Articles of Confederation, the complete agreement which defined that relationship was not finalized until the Tenth Amendment, the last amendment in the Bill of Rights, was ratified on December 15, 1791, just three years after the Constitution was ratified and two years after the national government was formed.

And it is the 28 simple words of the Tenth Amendment which defines federalism for us:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

When considering the “original agreement” of the Constitution, those first ten amendments must be considered part of the deal, because several states–Massachusetts being the most prominent–agreed to ratify the Constitution only on the solemn promise of proponents that the first Congress convened under the new government would add that Bill of Rights.

The motivation behind the 10th Amendment, as expressed vehemently during the debates held during the ratification conventions in the thirteen states, was to ensure that power didn’t become centralized in the national government. It was the same notion of “checks and balances” that had been the driving force behind James Madison’s original outline for the Constitution that was so influential at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

“The Constitution that was actually enacted and formally amended creates islands of government powers in a sea of liberty,” Georgetown Law Professor Randy Barnett wrote in his 2004 book Restoring The Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty.

Those government powers were balanced between the national government and the state governments.

“To better secure the natural rights of the sovereign people, the power of the national government was limited to those ‘herein granted’ in the written Constitution,” Barnett wrote in his most recent book, Our Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the People.

Under the Federalism defined in the Constitution, the national government has 33 specific limited and enumerated powers “herein granted” to its three separate branches.

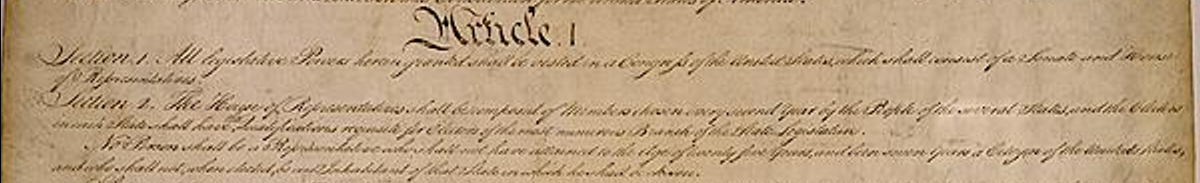

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution enumerates 19 specific powers granted to the legislative branch of the national government, one of the most important of which is the “Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises.”

Article II, Sections 2 and 3 of the Constitution enumerates 13 specific powers granted to the executive branch of the national government, the most significant of which states that “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States.”

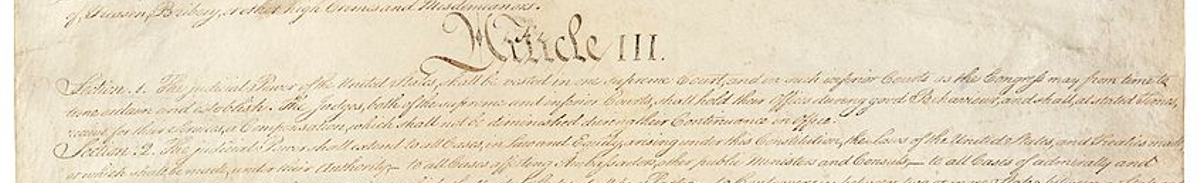

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution enumerates one specific power granted to the judicial branch of the national government: “The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority.”

It also defines 8 specific types of cases to which the judicial power of the judicial branch of the national government shall apply.

In tomorrow’s article on The Separation of Powers, we’ll explain how the Founding Fathers designed these three separate branches of the national government to provide “checks and balances” so that no one of the three branches would obtain powers so great as to make it capable of abusing those powers.

Here is the big important news about the foundational concept of Federalism within the United States Constitution:

Any powers other than these 33 enumerated powers specifically given to the national government’s three branches as identified above “are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people,” as the Tenth Amendment makes so clear.

You may note that we have been careful in this article to use the term “national government” rather than “federal government.”

This is intentional.

While it has been common practice for many years to refer to the “national government” as the “federal government,” this terminology leads to a great deal of confusion when it comes to understanding what the foundational concept of Federalism defined in the Constitution really means.

As the national government has extended its powers, particularly in the last century, far beyond the very limited scope defined in the Constitution, some people are under the misimpression that Federalism means the supremacy of the national or federal government over the state governments.

Similarly, the labeling of the different groups who debated the Constitution during the ratification process has added to the confusion surrounding the true meaning of Federalism.

Those who were most insistent on the inclusion of the Bill of Rights and the Tenth Amendment into the Constitution–like James Monroe and Patrick Henry in Virginia, and Samuel Adams in Massachusetts– were called “Anti-Federalists” while those who were initially resistant to the need for a Bill of Rights–and in this category we include both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison (the latter of whom subsequently experienced such a transformation during his successful 1789 campaign to win a seat in the House of Representatives that he ultimately became the legislative champion of the Bill of Rights)–were called “Federalists.”

So, it was really the “Anti-Federalists” who were ultimately responsible for the final form of Federalism incorporated in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Finally, there is the Federalist Party, the first political party in America. It was in existence from about 1792 until 1816, and it advanced policies that were often at odds with the foundational constitutional concept of Federalism.

It consisted of business and banking interests who supported the economic policies of Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of Treasury. Hamilton supported a national bank and the notion that the Constitution provided “implied powers” to the national government, a notion that the quickly formed second national party, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison vigorously disputed.

A great deal has happened in the 226 years since the Tenth Amendment was ratified, and most of it has advanced the power of the national government at the expense of state governments and individual citizens.

“Since the adoption of the Constitution, courts have eliminated clause after clause that interfered with the exercise of government power,” Georgetown Law Professor Barnett wrote in his 2004 book.

The result is just the opposite of what the Founding Fathers intended when they made Federalism one of the foundational principles of the Constitution.

“The judicially redacted constitution creates islands of liberty rights in a sea of governmental powers,” Barnett concluded.

What do you think?

Is it time to restore the foundational concept of Federalism the Founding Fathers installed within our Constitution to the operation of our national and state governments in 2017 and beyond?

And if it is, what specifically can be done to accomplish that?

In tomorrow’s article, we will talk about The Separation of Powers.

Three Things That Make the United States Constitution Unique in World History

Part Three: Separation of Powers

This is the third part of the second of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The Separation of Powers between three equal branches of the national government–legislative, executive, and judicial– along with Federalism are the two foundational concepts of the Constitution of the United States that protect the freedoms and liberties guaranteed to individual citizens.

Both foundational concepts are the practical implementation of the Founding Fathers’ belief in the need for checks and balances to prevent the rise of uncontrolled abuses of power within one branch of government.

“It is safe to say that a respect for the principle of separation of powers is deeply ingrained in every American,” the National Archives website says:

The nation subscribes to the original premise of the framers of the Constitution that the way to safeguard against tyranny is to separate the powers of government among three branches so that each branch checks the other two. Even when this system thwarts the public will and paralyzes the processes of government, Americans have rallied to its defense.

One Founding Father, more than any other, was the driving force behind the inclusion of The Separation of Powers as a foundational concept in the Constitution: James Madison, an intellectual giant who was only 26 years old when he arrived in Philadelphia in May 1787 to sit as one of fifty-five delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Young Madison, a graduate of Princeton University, came prepared. He had spent months reviewing other forms of government throughout history and arrived with voluminous notes and a detailed outline of how he thought the Constitution should be written. To a large extent, the final document followed much of that outline.

“Madison argues, it is not sufficient to establish separation of powers on parchment only. Because men are not angels—because they are so often actuated by private interest and ambition—these very motives themselves must be employed to keep the departments of government within their limited, constitutional boundaries,” the Heritage Foundation writes of the bookish young man who arrived in Philadelphia wise beyond his years.

“Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place,” the author of Federalist No. 51 wrote in early 1788 as the states were selecting delegates to attend the state conventions and debate the ratification of the Constitution. Madison probably authored that essay, though it may have been Alexander Hamilton.

“Madison thus proposed a system of checks and balances that would incorporate the less than sterling side of human nature into the very workings of government,” the Heritage Foundation notes:

To accomplish this, the powers of the three branches of government are partially blended, enabling each branch to guard against usurpations of power by the others and safeguard its own constitutional province. Examples of constitutional checks and balances include the executive veto of legislative bills, the legislative override of the executive veto, the required Senate confirmation of presidential appointments to the Supreme Court, and judicial review.

In essence, Madison wanted the different branches of government, as well as the two houses of Congress and the national and the state governments, to check each other in the exercise of power, thereby guaranteeing the diffusion of governmental power and the protection of the people’s rights and liberties.

“The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny,” James Madison wrote in Federalist Paper #47, first published in The New York Packet on February 1, 1788.

“The preservation of liberty requires that the three great departments of power should be separate and distinct,” he noted in that essay.

“Where the WHOLE power of one department is exercised by the same hands which possess the WHOLE power of another department, the fundamental principles of a free constitution are subverted,” he added.

The end result that emerged on parchment of this scheme of “checks and balances” known as The Separation of Powers designated specific powers to each of the three branches of the national government.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution enumerates 19 specific powers granted to the legislative branch of the national government:

(1) The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises,

(2) to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

(3) To borrow Money on the credit of the United States;

(4) To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

(5) To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

(6) To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures;

(7) To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States;

(8) To establish Post Offices and post Roads;

(9) To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;

(10) To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court;

(11) To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations;

(12) To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

(13) To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;

(14) To provide and maintain a Navy;

(15) To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

(16) To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

(17) To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;

(18) To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings;—And

(19) To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Article II, Sections 2 and 3 of the Constitution enumerates 13 specific powers granted to the executive branch of the national government:

Section. 2.

(1) The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States,

(2) he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices,

(3) and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

(4) He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur;

(5) and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law:

(6) the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

(7) The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.

Section. 3.

(8) He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient;

(9) he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them,

(10) and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper;

(11) he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers;

(12) he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and

(13) shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution enumerates one specific power granted to the judicial branch of the national government:

(1) The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;

It also defines 8 specific types of cases to which the judicial power of the judicial branch of the national government shall apply:

(1) to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;

(2) to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;

(3) to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;

(4) to Controversies between two or more States;

(5) between a State and Citizens of another State,

(6) between Citizens of different States,

(7) between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States,

(8) and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

Over the next 228 years, as Madison predicted “Because men are not angels—because they are so often actuated by private interest and ambition,” the checks and balances designated in the parchment of the Constitution has been transformed by the practices of non-angelic men and women to create a system of government that deviates substantially from the one envisioned by the Founding Fathers in two very specific ways:

First, the national government has continually usurped the power of the state governments, as envisioned in the foundational concept of Federalism.

Second, The Separation of Powers within the national government has evolved dramatically, as both the executive branch and the judicial branch have assumed greater and greater powers, while the legislative branch has abrogated–informally in many instances–some of its most important constitutional powers.

“Abrograte” is a strong word, not often used.

Dictionary.com defines its meaning as “to abolish by formal or official means; annul by an authoritative act; repeal,” or “to put aside; put an end to.”

It is in the nineteenth enumerated power in which the legislative branch has failed so dramatically:

To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

The legislative branch has given away huge powers to the executive branch in the form of specific regulatory rule making based upon laws passed in Congress. This sacrifice of authority has given rise, over the past century, to the runaway regulatory bureaucratic state.

The details of how this came about will be the topic of several articles in the remaining 25 articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series.

[…] noted earlier in this Constitution Series, the United States Constitution written by the fifty-five delegates to the Constitutional […]

[…] is the eighth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the fourteenth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up […]

[…] is the twelfth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the eleventh of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the tenth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the ninth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the eighth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the seventh of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the sixth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the fifth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the fourth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the third of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the third part of the second of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]

[…] is the second part of the second of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to […]