This is the eighth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The Separation of Powers and Federalism are two foundational concepts of the Constitution, based on the idea that checks and balances between competing interests will prevent any one individual or group from obtaining and exercising abusive powers within our republic.

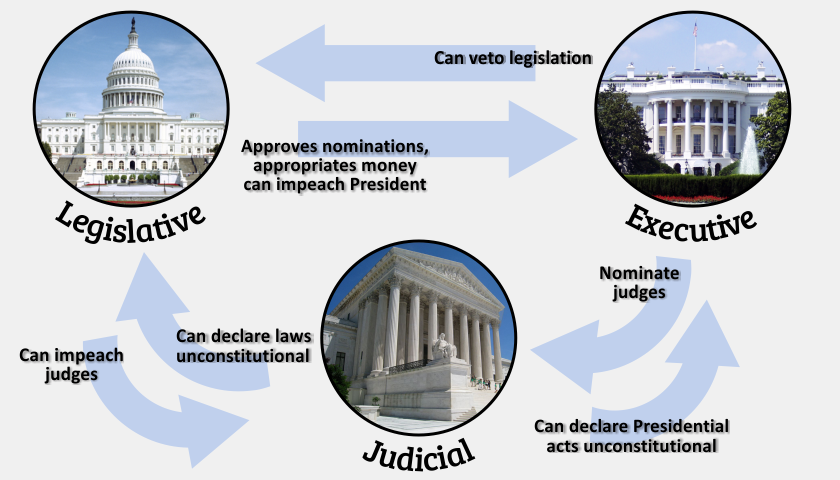

In the national government, the checks and balances of the Separation of Powers were designed within the Constitution, which gave specific powers to the three equal branches of government— executive, legislative, and judicial–but also placed limits on the powers of each branch.

The legislative branch, which passes laws, approves Presidential nominations for Cabinet positions and the Supreme Court and other federal courts, appropriates money, and can impeach the president and federal judges.

The executive branch can veto legislation, nominate judges, and administers the day-to-day operations of the government.

The judicial branch has asserted, without much resistance, the power to declare laws passed by Congress and Presidential actions unconstitutional–a principle commonly known as “judicial review.”

Unlike the powers granted the two other branches–the executive and the legislative–“judicial review” is not explicitly spelled out in the text of the Constitution, though it has become “one of the distinctive features of United States constitutional law,” according to FindLaw.com.

“It is no small wonder, then, to find that the power of the federal courts to test federal and state legislative enactments and other actions by the standards of what the Constitution grants and withholds is nowhere expressly conveyed,” FindLaw.com noted:

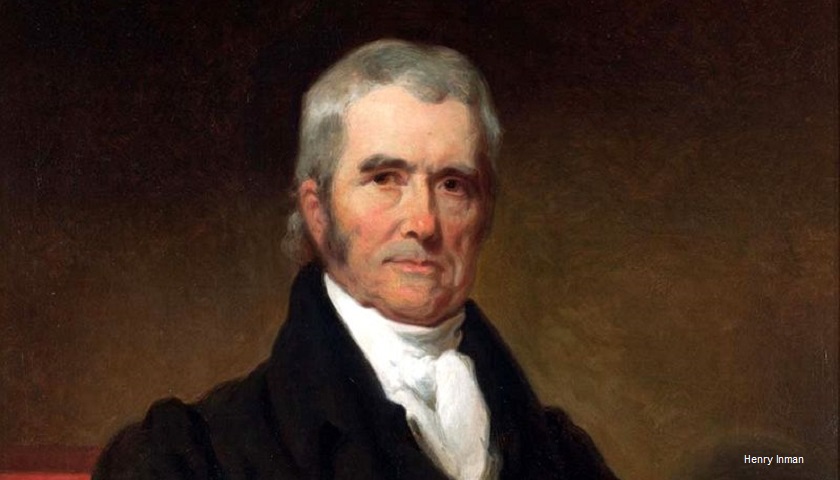

But it is hardly noteworthy that its legitimacy has been challenged from the first, and, while now accepted generally, it still has detractors and its supporters disagree about its doctrinal basis and its application. Although it was first asserted in Marbury v. Madison to strike down an act of Congress as inconsistent with the Constitution, judicial review did not spring full-blown from the brain of Chief Justice Marshall.

“Although judicial review is consistent with several provisions of the Constitution and the argument for its existence may be derived from these provisions, they do not compel the conclusion that the Framers intended judicial review nor that it must exist,” FindLaw.com concluded.

As University of San Diego Professor of Law Michael Rappaport, director of the Center for the Study of Constitutional Originalism, wrote in 2010, “judicial review is not just made up.”

“In recent years, scholars have argued persuasively that the Framers expected judicial review of the Constitution, ” he pointed out.

Still, since there is no specific text to explicitly support the concept of judicial review in the Constitution, our current acceptance of the principle derives from the precedent established in one peculiar case that did not seem particularly earth-shaking at the time the Marshall Court announced its decision on it in 1803: Marbury v. Madison.

“William Marbury, a self-made man and Adams loyalist, was one of the “midnight” justices whom John Adams appointed during his last days in office. The Federalist Senate confirmed his appointment on Adams’s last day as president, but after Jefferson assumed office and found that Marbury’s commission had still not been delivered, he ordered that it be withheld. Marbury subsequently sought from the Supreme Court a writ of mandamus that would compel Secretary of State Madison to deliver his commission,” Lynn Cheney wrote in her biography of the fourth president, James Madison: A Life Reconsidered:

John Marshall, a Virginia Federalist, former Secretary of State for President Adams, and staunch opponent of President Thomas Jefferson (despite the fact they were third-cousins), had become the nation’s fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court just two months before Adams gave Marbury his last minute position. Ironically, it was Marshall who had failed to deliver Marbury his commission when it was first issued by President Adams because he was still Secretary of State at the time – he held both offices concurrently for the last two months of the Adams administration.

Marbury did not sue Marshall, however, he sued James Madison, his successor as Secretary of State under President Jefferson, who also failed to deliver the commission.

“In 1803, the [Supreme Court] issued its opinion, saying that Marbury was entitled to the commission, but that the Supreme Court could not issue the writ [requiring Madison to deliver the commission] because the section of the Judiciary Act of 1789 that would have permitted to court to do so was unconstitution,” Cheney wrote:

On the surface, the outcome seemed positive for the Jefferson administration. But Marshall’s decision also allowed the chief justice to avoid direct confrontation with the administration, which was riding high, even while the president, whom he despised as only one Virginia cousin could another, had broken the law.

As Oyez.org framed the questions in the case:

(1) Do the plaintiffs have a right to receive their commissions?

(2) Can they sue for their commissions in court?

(3) Does the Supreme Court have the authority to order the delivery of their commissions?

The four members of the six member court who were present for the oral arguments in the case (Chief Justice Marshall, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, and Bushrod Washington were present. Alfred Moore and William Cushing were absent due to illness) unanimously decided in Marbury’s favor. There was, however, a twist to the case.

“Though Marbury was entitled to it, the Court was unable to grant it because Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 conflicted with Article III Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution and was therefore null and void,” Oyez.org noted.

“Of all the disappointed office seekers in American history, only William Marbury obtained the honor of having his portrait hang in the chambers of the United States Supreme Court. In the Justices’ small dining room designated by Chief Justice Warren Burger as the “the John Marshall room,” Chief Justice Burger placed the portraits of Marbury and James Madison, Marbury’s legal adversary, as if the two men, in partnership, had given the Chief Justice his commission to practice judicial review,” Professor David Forte wrote in his 1996 article, “Marbury’s Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury’s Appointment as Justice of the Peace. “

“Particularly in contrast with the annexation of Louisiana [in 1803], the decision handed down by the Supreme Court in Marbury v. Madison seemed at the time of little significance,” Cheney wrote.

But, as it turns out, it was of very great significance.

“The decision in Marbury v. Madison has never been disturbed, although it has been criticized and has had opponents throughout our history. It not only carried the day in the federal courts, but from its announcement judicial review by state courts of local legislation under local constitutions made rapid progress and was securely established in all States by 1850,” FindLaw.com noted.

The Justia US Law website identifies a total of 165 “acts of Congress held unconstitutional in whole or in part by the Supreme Court of the United States,” between 1803 and 2008.

“[T]he concept of judicial review has made the courts — and in particular the U.S. Supreme Court — the ultimate arbiter of whether a state or federal law violates the Constitution. Just as baseball umpires are sometimes criticized for their calls on the playing field, the exercise of judicial review has periodically exposed the Court to complaints that it has erred either by being too aggressive in striking down laws (in conventional parlance, “judicial activism”), or by not being aggressive enough in overturning laws (sometimes called “judicial passivity”),” Mark Pulliam wrote at National Review in 2015.

In the end, however, the standard for judicial review is left to the discretion the majority of the nine justices who serve on the Supreme Court.

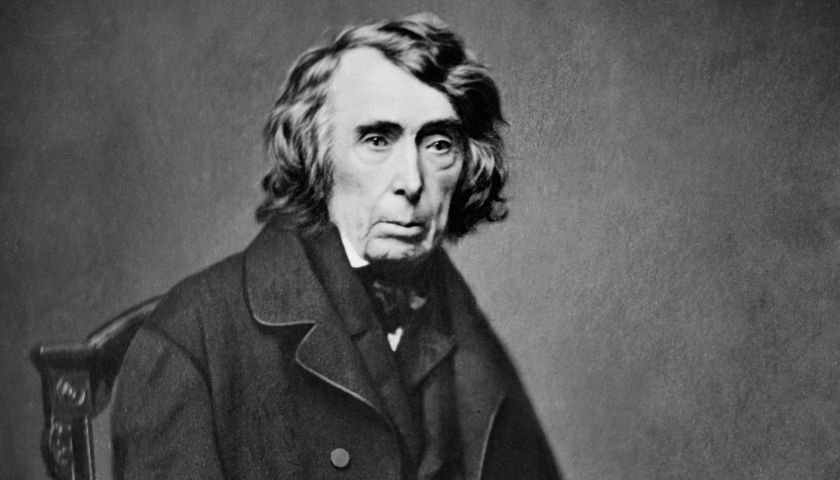

And sometimes when exercising this standard, they get it wrong, as they did the second time they struck down a law passed by Congress as unconstitutional fifty-four years after Marbury v. Madison. The Supreme Court used the power of judicial review in the 1857 Dred Scott decision, perhaps the worst decision ever made by the Supreme Court.

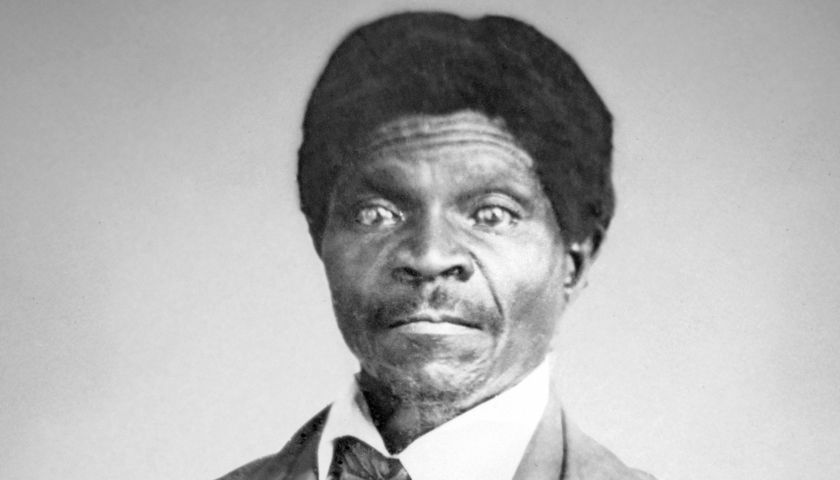

That decision declared the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional and returned Dred Scott, a slave whose owner brought him into free territory and consequently claimed his freedom, to slavery:

Not until 1857—fifty-four years after Marbury—was a second act of Congress declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. In the infamous Dred Scott case (Scott v. Sandford), the Court held that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional. This compromise—in addition to admitting Missouri to the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state—had divided the remaining U.S. territory along the 36°30° north latitude line. Slavery was “forever prohibited” above the line, except for Missouri. The Court ruled in 1857 that Congress lacked the power to exclude slavery from any territory. The decision intensified the debate over slavery, which eventually exploded into the Civil War. The Dred Scott ruling was undone by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, which outlawed slavery and extended equal protection under the law to all U.S. citizens.

In March 1861, during his first inaugural address, President Abraham Lincoln indirectly criticized the exercise of judicial review by the Supreme Court in the Dred Scot decision, an error that helped plunge the country into the Civil War:

I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court, nor do I deny that such decisions must be

binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit, while they are also entitled to very high respect and consideration in all parallel cases by all other departments of the Government.And while it is obviously possible that such decision may be erroneous in any given case, still the evil effect following it, being limited to that particular case, with the chance that it may be overruled and never become a precedent for other cases, can better be borne than could the evils of a different practice.

“At the same time, the candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent

practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal,” Lincoln concluded.

One hundred and fifty years and more than 150 Supreme Court rulings in which judicial review has been exercised later, the principle remains controversial.

“Our supreme law – ratified by the states and binding on succeeding generations – is the Constitution (not the Declaration of Independence). The Constitution embodies legitimate rights, which the courts are not just permitted, but obligated, to enforce. At the same time, the Supreme Court has invented many “rights” that appear nowhere in the Constitution and are, in fact, entirely the product of the justices’ own personal predilections,” Pulliam wrote in his 2015 National Review article:

If a legitimate constitutional right is implicated, a court does not engage in “activism” by striking down a law that violates it. That is the court’s duty. Indeed, the court would be guilty of passivity (or outright abdication) if it upheld the law. Courts are supposed to uphold laws that do not violate a legitimate constitutional right, no matter how foolish the judges may think they are. That is exercising “judicial restraint” (a good thing). Conversely, if a court fails to strike down a law that does violate the Constitution (as the Supreme Court arguably did with Obamacare in NFIB v. Sebelius [2012]), it is not engaged in “judicial restraint,” but is guilty of passivity/abdication (a bad thing). However, giving the Court carte blanche to overturn laws for reasons not grounded in the Constitution invites judicial usurpation, which is both unprincipled and undemocratic.

With the current Supreme Court divided between four “conservative” originalists, four “liberal” living Constitution proponents, and one swing vote, the death of the leading originalist on the Court in 2016, Antonin Scalia, set off a political firestorm that displayed the kind of checks and balances envisioned by the Framers.

Then-President Obama, a Democrat, nominated Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court, a well-respected jurist whose ideology clearly fit within the “liberal” living Constitution proponents. Replacing an originalist with a liberal would have dramatically changed the court’s balance, in which a number of 5-4 cases were decided by the “swing” vote, Justice Anthony Kennedy.

The Republican controlled Senate, led by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky), refused to confirm or even hold hearings on Garland’s nomination.

With the Presidential election of 2016 looming, the Republicans argued, let the next President elected by the American people pick this ninth critical Supreme Court justice.

When Republican Donald Trump won that election, he quickly nominated an originalist, Neil Gorsuch, to succeed Justice Scalia on the Supreme Court.

The Senate, still controlled by the Republicans, confirmed Gorsuch in 2017, but only after they took advantage of a new reading of the Senate rules introduced only a few years earlier by the Democrats, which allowed them to break a filibuster by the Democrats.

The entire process was dramatic and contentious, an example of just the sort of checks and balances the Framers had in mind at the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

When another opening comes in the Supreme Court, you can bet another round of checks and balances drama will take place.