by Anders Edwardsson

Today, saying that America is exceptional has become a controversial statement. With the claim that America is a deeply racist and terrible country, American exceptionalism is lambasted as a myth.

But few today know the origins of American exceptionalism and its place as the main storyline of U.S. nationalism. And yet, it’s only by examining the history of this idea that we can have an informed opinion on the issue. So, what is the history of American exceptionalism?

Nationalism

While it didn’t cohere until the 1800s, American exceptionalism is the prominent form of U.S. nationalism, so in order to understand American exceptionalism, we have to go back to the origins of nationalism before the New World was even discovered.

At its core, nationalism is simply a bundle of ideas, tales, and symbols that bridge social, economic, and other divides and create feelings of national pride and unity. Modern nationalism didn’t appear until the 18th century. But thousands of years before then, hunter-gatherers told tales about ancestors’ deeds and visions to guide behavior, define everyday duties, and more.

As civilization progressed, kings and other politicians saw that more elaborate national stories were advantageous, and they figured out that these stories could be used to buttress governments robust enough to make larger states and empires possible.

Early America

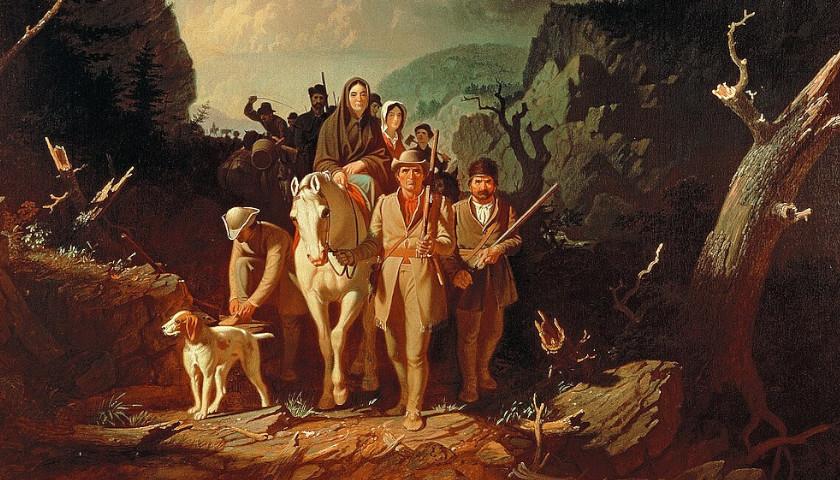

American exceptionalism didn’t fully develop and cohere until later in American history, but aside from its roots in nationalism, it has a foundation that started in 16th-century North America with the settlers from the British Isles. These settlers formed a culture based on English particulars like the common law system, independent courts, and sharing political power. And as a result, in the 13 Colonies, people identified as Englishmen.

Because the settlers were so far from the British Isles, they held tightly to the aspects of their homeland that they could. Thus, the English freedom tradition stemming from the Magna Carta became more pronounced in America than in England. And when the Founding Fathers wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776, most of it became a list of complaints concerning the king and Parliament’s un-English behavior—and the American Revolution that followed aimed to protect the colonists’ rights as free “Englishmen.”

Still, the Founders did not create a European-like country with a king, nobility, and state church. Instead, they combined English freedoms with ancient Greek, Roman, and medieval wisdom, plus contemporary Enlightenment thinking, into a new sociopolitical order. In 1789, the U.S. Constitution created a political system with a small national (federal) government purposely designed to protect a free economy and high levels of personal freedom.

To support independence and merge regional colonial identifications into a national identity, several key questions had to be asked: Why should America be one nation? Why did America deserve freedom? Why was America an excellent place to live?

The answers drew from several sources prominent in England—including Biblical themes, a 12th-century Arthurian tale about Britain as the place Joseph of Arimathea chose to hide the Holy Grail, and rhetoric from the Tudor Era about England being God’s “elect nation.” Americans, therefore, saw their country as a new promised land and believed God had designated the U.S. for higher purposes.

This view combined with a high regard for the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to form American exceptionalism. The idea was that America was a unique country that presaged a future where limited governments protected freedom and human rights worldwide.

Moreover, since most endorsed the Founders’ views of the U.S., the political themes of American exceptionalism—small government, low taxes, few regulations, state rights, and a free economy—were supported by nearly everyone. American politicians even competed to live up to the Founders’ ideals and kept the country’s original socioeconomic order untouched.

The 1800s and 1900s

For over a century, most saw America’s role as a model, not an implementor, of freedom. Hence, the U.S. did not invade other countries to change them. Or, as future President John Quincy Adams said in 1821, America “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.”

Two things eventually changed this. First, as the size, natural resources, and vibrant economy made the U.S. rich, politicians couldn’t resist turning the country into a world power. Second, at the end of the 19th century, some politicians—inspired by European ideas—argued that government control over economic and social realities could improve people’s lives. Both these developments passed a tipping point soon after 1900 and set the U.S. on track toward today’s dual warfare-welfare state.

All told, American exceptionalism helped drive colonists’ demand for independence from England and developed into the country’s leading national story. And until modern times, it played a double role as a bipartisan policy program and an intellectual blueprint for how people should think and behave as Americans. Despite the contemporary vilification of American exceptionalism, America as we know it today—and the freedoms we have as Americans—are intertwined with this perspective on America and its place in the world.

– – –

Anders Edwardsson is a contributor to Intellectual Takeout.