by Kevin Killough

BlackRock began renaming environmental, social and governance (ESG) earlier this year. It’s now calling it “transition investing.”

The company recently updated its climate and decarbonization stewardship guidelines. The document makes no mention of ESG, but it shows in many ways, the world’s largest investment manager with $10 trillion in assets under management is still pursuing many of the same goals.

When the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted final rules regarding climate disclosures in March, critics were partially relieved that the most stringent aspects of the proposed rules weren’t included. The rule still faces a number of legal challenges by parties who argue the rules violate the First Amendment, the SEC exceeded its authority, and compliance will drive up costs and hurt consumers.

When it comes to government actions, people normally have recourse to legal process to review their complaints. One of the main criticisms of ESG is that it pushes progressive policies through a process that circumnavigates elected officials and the courts. When investment firms require banks, for example, to meet certain ESG “sustainability goals,” capital in the market gets bound up with leftist political objectives through administrative rulemaking.

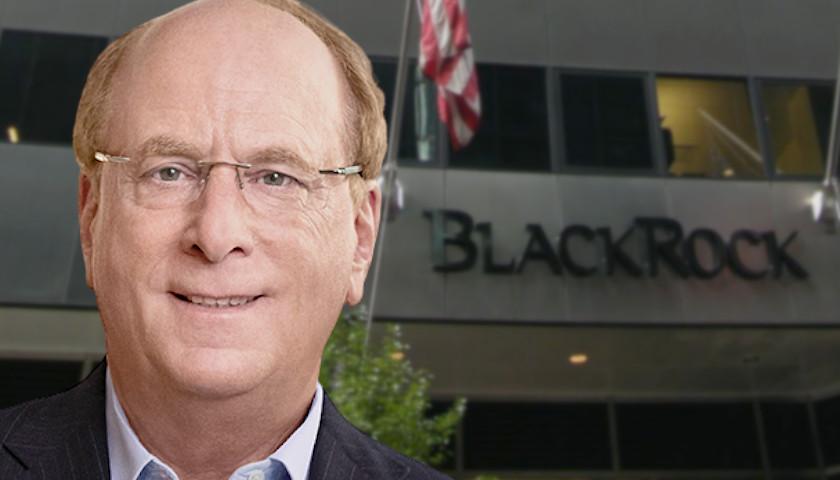

The ESG movement has received a lot of pushback over the past couple of years from state legislatures and Congress. The various efforts have gotten ESG proponents’ attention. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink told Reuters last year he was avoiding the use of the word “ESG.”

However, critics say that, far from being in retreat, the movement has just rebranded and regrouped. Its goals remain the same, but they’re being pursued under different strategies.

Tom Jones, head of the American Accountability Foundation, told Just the News that you can’t discount the successes that have been seen in Texas and other states that have passed anti-ESG legislation.

However, “for every Texas, there’s a CalPERS,” Jones said, referring to the California Public Retirement System fund, which has nearly $500 billion in assets under management. That organization attempted last month to oust the Exxon board over a lawsuit the company filed against activists groups.

BlackRock has been one of the most vocal proponents of ESG and a prime target of its critics. The company’s updated climate stewardship guidelines reflect its new “transition investing” branding. The guidelines target funds with combined assets of $150 billion for more scrutiny to ensure they are aligned with BlackRock’s strict climate goals.

It requires companies to disclose their decarbonization strategy to demonstrate it can achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. This includes not only the Scope 1 and 2 emissions targets, which were part of the SEC’s final climate disclosure rule, but also Scope 3 emissions, which were part of the SEC’s stringent proposed rules. The Scope 3 requirements weren’t in the final rules.

Scope 1 emissions are direct greenhouse (GHG) emissions that occur from sources that are controlled or owned by the company, and Scope 2 emissions are indirect GHG emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat, or cooling.

Scope 3 are those emissions along the entire supply chain that indirectly impact its products or services. For example, if a bank provided agricultural loans, Scope 3 emissions might include the emissions from a farming operation that receives a loan from that bank. To comply with such standards, a bank might require farmers that receive loans to implement “sustainability” initiatives to lower the farm’s emissions.

Gathering the data to disclose this information is costly, as are the programs this hypothetical farmer would have to implement to satisfy the bank’s requirements, which the bank would have to require to meet ESG requirements.

The Buckeye Institute, a free-market think tank, released a report earlier this year estimating the cost of compliance with net-zero emissions policies and corporate ESG reporting requirements on American farms. According to the report, farmers will see costs rise at least 34%, which will translate to annual grocery bills rising by 15%.

BlackRock’s updated decarbonization guidance initially applies to investments that have “explicit decarbonization or climate-related investment objectives.” There are currently 83 Europe-based funds on the list that will receive the extra scrutiny, but Bloomberg reports that the requirements may be extended to funds in the U.S. and Asia-Pacific region. With Scope 3 emissions scrutiny included, the guidelines could impact companies outside the list.

The problem for anti-ESG lawmakers looking to keep the movement from impacting state investments is how to define what ESG is when its name changes. Jones with American Accountability Foundation referred to Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s description of obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

“You know what these guys are doing. So if they’re engaged in this kind of behavior, no matter whether they call it sustainable investing, renewable investing — whatever they want to call it — it’s still at the end of the day using state investment funds for political purposes,” Jones said.

– – –

Kevin Killough is a reporter for Just the News.

Photo “Larry Fink” by BlackRock. Background Photo “BlackRock Headquarters” by Americasroof. CC BY-SA 3.0.