MURFREESBORO, Tennessee – 272,000 legal immigrants arrived in the United States during 2016 with an entitlement to the full menu of welfare programs, just like any U.S. citizen, attendees were told at the Conservative Caucus in Murfreesboro on Saturday.

The information was presented by one of the afternoon’s speakers, Don Barnett, a fellow with the Center for Immigration Studies who has followed refugee resettlement for over 20 years.

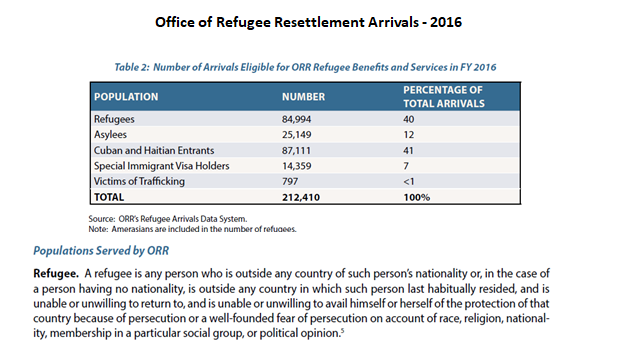

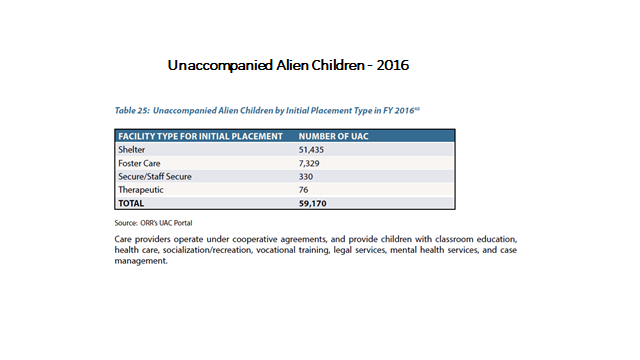

The legal immigrants consist of refugees, asylees, Cuban and Haitian entrants, special immigrant visa holders, victims of trafficking – a relatively new category, as well as unaccompanied alien children.

The legal immigrants consist of refugees, asylees, Cuban and Haitian entrants, special immigrant visa holders, victims of trafficking – a relatively new category, as well as unaccompanied alien children.

While well-intentioned humanitarian immigration is one story, Barnett says the policies have a huge influence on the flow of illegal immigrants into the country.

In fiscal year of 2019, the Border Patrol encountered nearly 1 million individuals trying to cross the southwest border, the majority of whom gave themselves up to border officials and claimed asylum. After six months,these asylum claimers can receive a Social Security number and work authorization, while they await their day in court which could take more than a year.

Barnett reported that about 400,000 work permits were given out in 2019 to those waiting for an asylum hearing.

When it comes to the use of welfare by refugees, a review of those in the country for a period of 4.5 to 6.5 years shows that 25 to 30 percent are on some type of cash assistance and more than 50 percent receive non-cash assistance of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistant Program).

The fiscal 2019 Office of Refugee and Resettlement budget and refugee expenditures of the State Department was about $2.2 billion. However, the total cost of the refugee resettlement program is about 10 times higher because official cost estimates never include the cost of public assistance.

The fiscal 2019 Office of Refugee and Resettlement budget and refugee expenditures of the State Department was about $2.2 billion. However, the total cost of the refugee resettlement program is about 10 times higher because official cost estimates never include the cost of public assistance.

This, Barnett says, is despite the fact that the biggest cost of the program, by far, is the welfare usage.

Access to welfare was one of the most important developments in the U.S. refugee policy of the Refugee Act of 1980 co-sponsored by then-Senator Joe Biden.

The humanitarian immigration policy has drifted from its original intent and expanded, Barnett says, due to the actions of all three branches of government as well as the influence and lobbying of profitable federal contractors, the cheap labor lobby, the chamber of commerce and an organized and well-funded global professional left.

Barnett pointed out that the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition (TIRRC) located right in Nashville is part of that professional left that lobbies the legislature effectively with a paid staff of 14 and gets millions from well-known left-wing foundations.

TIRRC is in a partnership with Conexion Americas housed in Casa Azafran on Nashville’s Nolensville Pike, along with other partners such as American Muslim Advisory Council, the American Center for Outreach that aims to bring the Muslim voice to the political stage with the objective of changing the local political debate; and the Randy Boyd-funded Mesa Komal Kitchen.

A driver of the program was the metamorphosis of charities that had been subject to limits and incentivized to seek true assimilation and economic integration without entitlement to welfare programs into money-making federal contractors, Barnett said.

Today, the refugee industry including Catholic charities can claim that most refugees are “self-sufficient within six months.” Barnett reported.

That’s because the federal government changed the meaning of “economic self-sufficiency” for refugees, Barnett advised, so that an individual that is on food stamps, on Medicaid, in public housing and in various other public assistance programs is officially considered “self-sufficient.”

Another problem with the money-making federal refugee contractors is that it is difficult to get information from the very secretive program of Catholic charities who took over when the State of Tennessee got out of the program.

Another problem with the money-making federal refugee contractors is that it is difficult to get information from the very secretive program of Catholic charities who took over when the State of Tennessee got out of the program.

Barnett presented somewhat outdated but the most recently available information from 2010 and 2011 which shows that TennCare enrollment of refugees in those years was 834 and 682, respectively, reflecting 48 percent and 58 percent participation. For those not in TennCare, they received eight months of private health insurance.

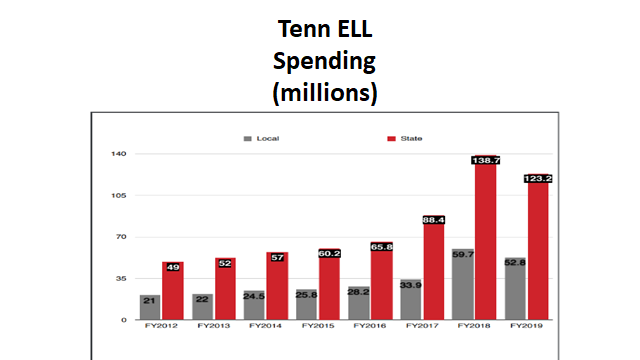

Another tremendous cost, although not totally related to refugees, is the state’s spending on English Language Learning (ELL), which Barnett reported at $123.2 million for the state and $52.8 million at the local level.

According to Barnett, a comprehensive study done in 2017 by the Department of Health and Human Services, but not released, looked at all humanitarian arrivals from 1980 on and traced their fiscal impact over the ten-year period of 2005 to 2014 and found that refugees, special immigrant visa holders and asylees are:

- More than twice as likely to be in SSI (Supplemental Security Income) than the average American

- Twice as likely to be using EITC (Earned Income Tax Credit)

- Twice as likely to be using WIC (Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children)

- In SNAP at a rate of 21 percent versus the U.S. average of 15 percent

- More than twice as likely to be using public housing credits or in public housing

- 50 percent more likely to be in TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families)

- 50 percent more likely to be in Medicaid

- In poverty at a rate of 19 percent versus the national average of 14 percent

Barnett explained that many of the federal welfare programs require a state contribution toward the total cost of the program, with the largest state portion being TennCare, the state’s version of Medicaid, where Tennessee pays 35 percent of the cost.

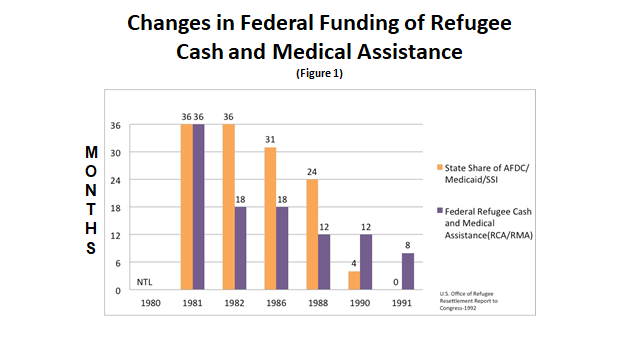

The Refugee Act of 1980 was meant to be paid for by the federal government, with reimbursement to states for the costs incurred for hosting refugees.

The promise of federal financial support was crucial to getting the Refugee Act passed. In fact, said Barnett, some congressmen admitted that a portion of the funding formula covering the program for three years was inadequate for the actual cost and argued for a longer time period of federal support.

Barnett presented a graph demonstrating that as soon as the Refugee Act became law, the federal government began withdrawing its financial support, which shifted the costs to the states. By 1991, all federal support for state costs related to welfare programs had ended and the second stream of support was reduced from 36 to 8 months.

The ability of the state to exit the program ended, Barnett said, when a 1994 regulation allowed the private contractors to continue operations in a state, even when the state officially withdrew from the program.

The ability of the state to exit the program ended, Barnett said, when a 1994 regulation allowed the private contractors to continue operations in a state, even when the state officially withdrew from the program.

In effect, the program became one that a state could never leave, yet still had to pay for, said Barnett.

If a state opts out of a program and the program continues by another means using state funds, Barnett suggests that violates constitutional principles preserving state sovereignty over its own resources.

A bill introduced in the second session of the 111th Tennessee General Assembly by Rep. Ron Gant (R-Rossville) sought to deal, in part, with this issue.

It also would have prohibited Governor Bill Lee from making decisions or obligating the state in any way with regard to refugee resettlement without authorization by the General Assembly, as the governor he declared he would do in December 2019.

Unfortunately, the bill was one of many conservative measures left unaddressed by the Senate, even though the House got the legislation through to scheduling for a floor vote.

When the Supreme Court struck down the Obamacare provision requiring states to expand Medicaid, Chief Justice Roberts said, “The States are separate and independent sovereigns. Sometimes they have to act like it.”

That’s where the conservative State Rep. Terri Lynn Weaver (R-Lancaster) comes in. Weaver championed SJR467 through the House in 2016, which directed “the commencement of legal action, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief from the federal government’s mandated appropriation of state revenue and noncompliance with the Refugee Act.”

The resolution, which passed in 2016 overwhelmingly in both chambers, called for the Tennessee Attorney General to initiate or intervene in the civil actions or seek appropriate federal relief on behalf of the state.

At the time, Weaver questioned then-Governor Bill Haslam in a letter she addressed to him about what he is doing to defend the Constitution, telling him that Tennesseans are looking for a leader.

“Lead us,” Weaver said in concluding her letter to Governor Haslam.

The resolution she championed was returned to the legislature without the signature of Haslam.

She said that the legislature went on without the blessing of Haslam and Attorney General Herbert Slatery. In fact, she said, “They did everything they could to stop us.”

The Thomas More Law Center (TMLC), a national non-profit public interest law firm based in Ann Arbor, Michigan agreed to represent Tennessee without charge. Weaver is named as a plaintiff in the lawsuit.

TMLC filed a certiorari petition to the U.S. Supreme Court in March of this year, to overturn a Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision that the Tennessee General Assembly does not have the institutional standing to challenge the constitutionality of the refugee resettlement program.

In terms of Gant’s bill, . Weaver said it had 60 co-sponsors in the House, where it passed “lickety-split and ran straight into a Senate wall.”

She continued, “This is where, we as members of the state legislature, really do need to rely on your engagement.” She also invoked President John Kennedy’s famous quote, “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.”

Weaver said she loves that statement, and called on Caucus attendees to reach out to their State Senators and House legislators on the issues discussed over the course of the day.

Weaver concluded her comments with her inspiring rendition of the not well known fourth verse of The Star Spangled Banner.

– – –

Laura Baigert is a senior reporter at The Tennessee Star.

Photo “Citizenship Paperwork” by Grand Canyon National Park. CC BY 2.0.

This policy is absolutely crazy.