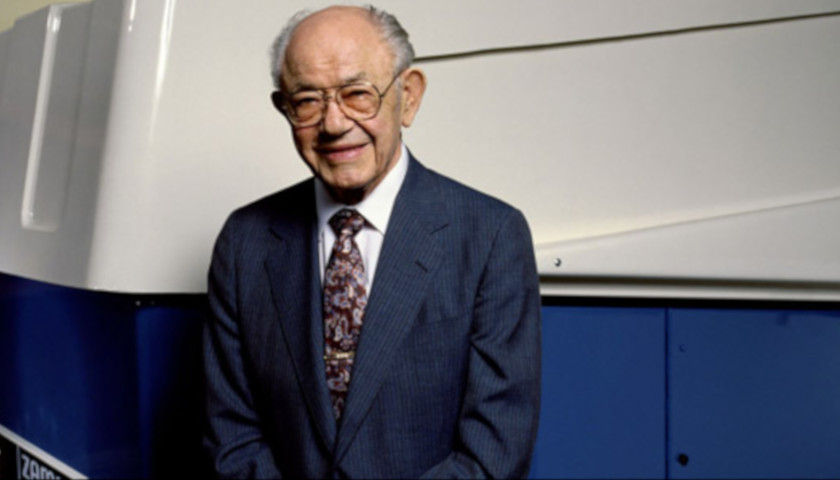

Frank Joseph Zamboni never played a second of professional hockey, but he was still inducted into the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame in 2009 for his vital contributions to the sport.

The son of Italian immigrants, Zamboni was born on January 16, 1901 in Eureka, Utah. Shortly after his birth, Zamboni’s parents relocated the family to Lava Hot Springs, Idaho where they had purchased a farm. At the age of 15, Zamboni was pulled from school so he could help his father on the family farm and began working on the side as a mechanic in a local garage, according to a family history written by Joseph Scafetta, Jr.

His parents sold their Idaho farm in 1920 and moved with their three youngest children to California to be close to their eldest son, George, who ran an automobile garage outside of Los Angeles. Zamboni and his younger brother, Lawrence, worked for their older brother at his garage and picked up work at a blacksmith shop on the side.

In doing so, they saved up enough money to send Zamboni to Chicago’s Coyne Trade School, where he studied to be an electrician. Upon graduating in 1922, he returned to California and opened up the Service Electric Company with Lawrence. The two specialized in electrical work, drilling water well, and installing water pump equipment for dairies, Scafetta writes.

In 1924, Zamboni’s company was approached by the New Way Electric Company with an electrical issue. The collaboration sparked a series of patents Zamboni obtained for electrical resisters and coils. Zamboni received 15 patents throughout his lifetime, and the first three were related to electrical improvements.

Zamboni and his brother expanded into the ice-making industry in 1927 and built a plant “that made the block ice wholesalers used to pack their product that was transported by rail across the country,” according to a company history of Zamboni’s life. Willis Carrier’s air conditioning and refrigeration inventions, however, caused the demand for block ice to shrink.

So the Zambonis sold their block ice business in 1939, but kept their refrigeration equipment, which they used to build one of southern California’s first ice rinks.

The Zamboni brothers and their cousin Peter opened Iceland Staking Rink in Paramount, California in 1940, and the rink still operates today just blocks from the current Zamboni factory. At the time of its opening, the ice rink was “one of the largest rinks in the country with 20,000 square feet of skating surface,” Scafetta notes.

“The 100 by 200-foot open-air arena could accommodate 800 skaters. In May 1940, a dome was added to protect the floor from the warm southern California sun. Approximately 150,000 skaters used the rink yearly,” he continues.

The obvious challenge of running an ice rink was maintaining the quality of the surface. One of his first innovations (which he received a patent for in 1946) was a method for reducing ripples on the surface of the ice usually caused by pipes beneath the surface.

But Zamboni’s main frustration was the amount of time it took to resurface the ice. The company notes that “resurfacing the ice meant pulling a scraper behind a tractor, shaving the surface. Three or four workers would scoop away the shavings, spray the surface with water, and squeegee the dirty water away.”

The process took well over an hour to complete and cut away at quality skating time. So Zamboni bought a tractor in 1942 to begin experimenting with new ways to resurface the ice. After several years of experimentation, Zamboni finally had completed his “Model A Zamboni Ice Resurfacer” by the late 1940s. For this invention, Zamboni received his most “basic and broadest” patent for an ice resurfacing machine. He had created the prototype for future Zambonis.

Scafetta describes the Model A like this:

“Essentially a sharp-edged blade shaves the surface of the ice. After a horizontal screw gathers the shavings, a conveyor (now a vertical screw) propels the shavings into a snow tank. Water is then fed onto the ice from a second tank and a squeegee-like conditioner flushes dirt and debris out of any remaining grooves and indentations in the ice. Next, the dirty water is vacuumed up, filtered and returned to the second tank. Finally, the rink floor is renewed when clean hot water is spread on the ice by a towel behind the conditioner and then is frozen.”

Zamboni would go on to create the Model B, C, D, and E—a testament to his continued drive to improve his invention, but also the many obstacles he encountered. By the mid 1950s, there “was so much demand for the new fangled machine that he opened a second manufacturing plant in Brantford, Ontario, Canada” as well as a sales office in Zurich, Switzerland.

There’s debate among historians as to when a Zamboni machine was first used in an NHL game, but the company believes it was on New Years Day in 1954 during a Boston Bruins game at Boston Garden.

Zamboni applied his innovations to baseball as well and created the Astro Zamboni, which sucked up water from the field and pumped it off the turf. He received two patents for his improvements to the game of baseball.

The Zamboni ice resurfacing machine made its debut at the Winter Olympic Games in 1960 in Squaw Valley, California. They were the first games to use a mechanical ice resurfacer, and six Zambonis maintained all of the ice rinks.

Zamboni died at the age of 87 in Long Beach, California on July 27, 1988. His wife of 65 years, whom he had married in his early 20s, died two months earlier.

– – –

Anthony Gockowski is managing editor of Battleground State News, The Ohio Star, and The Minnesota Sun. Follow Anthony on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected].

Photo “Frank Zamboni” by Zamboni.com.