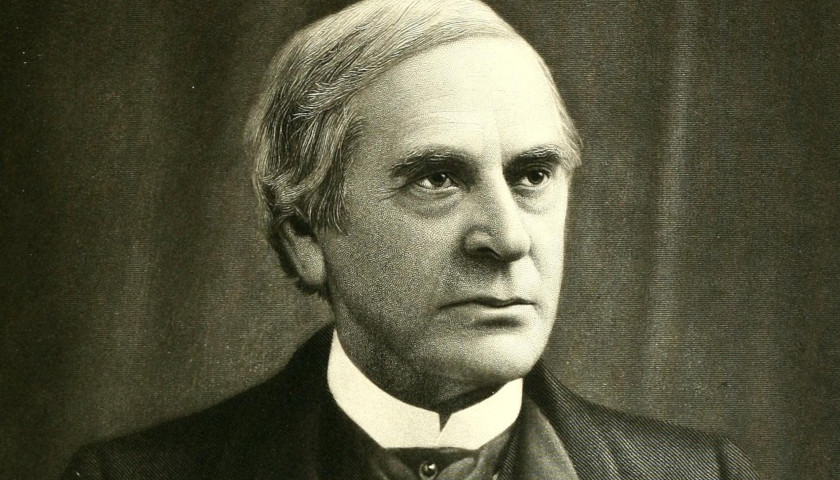

George Henry Corliss’ steam engine powered the Industrial Revolution and solidified steam as the superior source of power over waterpower.

“The name of [James] Watt easily takes the place of first importance in the history of the steam engine—and probably the name of George H. Corliss would, by general consent, be given the second place. The importance of his inventions, and the excellence of his engineering achievements, is remarkable when we consider how little his inheritance and his early associations contributed to that end,” Dwight Goddard wrote of Corliss in a 1905 book, Eminent Engineers.

Early life

Corliss was born on June 2, 1817 in Easton, New York on the border of Vermont. His father was a physician and he attended school until the age of 14, when decided to drop out and begin working as a clerk in a factory store. He returned to school, attending an academy in Vermont, and eventually opened up his own general store in 1838 at the age of 21.

According to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, he received a number of complaints about poorly stitched shoes and so he decided to invent his own sewing machine for stitching leather. He received a patent for the machine in 1842.

But the earliest display of his inventiveness came when a flood washed away one of the only convenient bridges in Greenwich, New York.

“The local builders declared it impossible to erect even a temporary bridge for weeks to come. Young Corliss constructed an emergency bridge in ten days at an expense of only fifty dollars,” Goddard explains.

At the age of 27, he moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where he began working as a draftsman for Fairbanks, Bancroft, and Company in their steam engine and boiler manufacturing firm. He quickly climbed the ranks and later left the company to enter into a partnership as a senior partner of Corliss, Nightingale, and Company, which was eventually incorporated under the Corliss Steam Engine Company in 1856.

It was while working as a senior partner of this new company that Corliss came up with his improvements to the steam engine.

The Corliss Engine

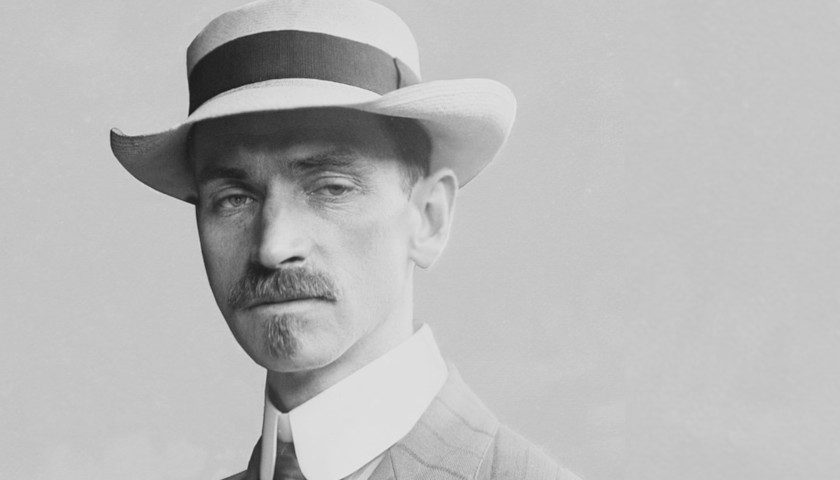

Thanks to Corliss’ inventions, steam power overtook waterpower as the superior source of energy for American industrialists. But the development of the steam engine was a century-long process.

In 1712, British inventor Thomas Newcomen invented the world’s first steam engine. More than 50 years later, Scottish inventor James Watt designed improvements to Newcomen’s creation, inventing a condensing chamber that prevented steam loss and allowed the engine to run continuously.

In the late 1840s, the 30-something Corliss improved on Watt’s design by creating a “steam engine that offered superior fuel consumption and smooth running speeds.”

The Henry Ford Museum describes the invention as such:

a unique system of four separate rocking valves (two for intake, two for exhaust) that permitted steam to quickly pressurize inside a cylinder, push down a piston and then be expelled before it cooled and condensed, conserving precious engine heat. He also designed an automatic variable cutoff valve, allowing the speed of the engine to be determined by the load placed on it.

This “automatic drop-cutoff” efficiently controlled the amount of steam entering the cylinder and became the standard among American and British manufacturers alike. He also created a valve gear that made the “engine extremely efficient in steam consumption and was the most efficient system for controlling low to medium speed engines,” according to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

In an essay on the Corliss engine, Nathan Rosenberg and Manuel Trajtenberg explain the battle between water power and steam power. On the one hand, water power “offered abundant and cheap energy, but restricted the location of manufacturing just to areas with propitious topography and climate.” Steam engines offered the “possibility of relaxing this severe constraint.”

They argue that the Corliss engine actually “served as a catalyst for the massive relocation of industry away from rural areas and into large urban centers.” In other words, the Corliss engine powered the Industrial Revolution.

“His innovations significantly increased fuel efficiency, a key step in the transition from water to steam power that marked the Industrial Revolution,” says the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Centennial Exhibition

The most iconic moment of Corliss’ career as an inventor came in May 1876 during the Centennial Exhibition at Machinery Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Famed inventors such as Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison were in attendance, but Corliss stole the show with his unveiling of the Centennial Engine.

On the opening day of the ceremony, Corliss “invited the event’s most famous guests—President Ulysses S. Grant and a foreign diplomat beloved by Americans, Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro—to pull the twin levers to start the motors.”

“Corliss had located the noisy boilers in an adjacent building, so when the 1,400-horsepower steam engine started up, spectators were astonished. All the machines in the immense hall began to run, powered by the Corliss engine through shafts that totaled more than a mile in length. And yet, unbelievably, the giant engine operated silently, as if by magic,” the Henry Ford Museum writes of the affair.

Corliss’ Centennial Engine powered all of the machinery in Machinery Hall for the duration of the six-month expo.

“It stood forty feet tall and weighed six-hundred-tons, making it the largest steam engine, and based on its maximum power rating, the most powerful at the time,” says the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Legacy and Awards

Corliss was highly celebrated during his lifetime. He received a gold medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition, a global competition with more than one hundred other inventors, and the Rumford Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1870.

He held an honorary M.A. from Brown University and was made an “Officer of the Order of Leopold” in 1886 by the King of Belgium. He even had a brief stint as a state senator from 1868 to 1870.

In one case, Corliss won the top award at the 1873 Vienna Exposition, even though he didn’t officially enter any of his inventions. The judges apparently concluded that since Corliss’ innovations were used in most of the steam engines on display, he should receive the top prize.

Corliss died on February 21, 1888.

– – –

Anthony Gockowski is managing editor of Battleground State News, The Ohio Star, and The Minnesota Sun. Follow Anthony on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected].