by Robert Romano

Recession warning lights are flashing predictably after the Federal Reserve has finally ended quantitative easing – it’s now dumping $50 billion of government and mortgage bonds a month – and short-term interest rates have risen.

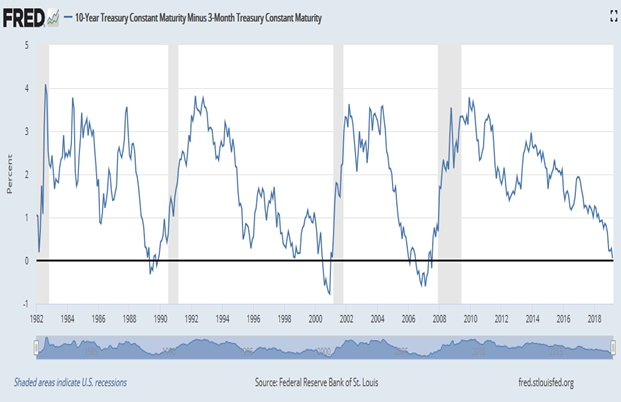

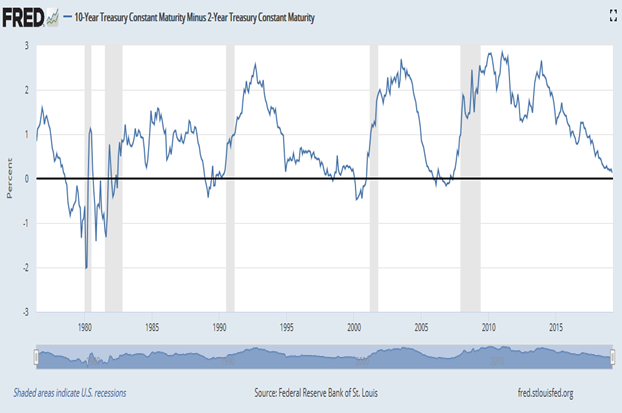

The 10-year-3-month treasuries spread inverted on March 22, and the 10-year-2-year and the 10-year-federal-funds-rate do not appear to be far behind from inverting.

When interest rates invert, it means the interest rate on short-term bonds is higher than the rate of return for long-term bonds, meaning there is slightly more demand for the long-term bonds, which are viewed as a relatively safer investment.

So, how did we get here? The short answer is that since the Fed began dumping bonds back on the market – it has shed $458 billion since Sept. 2017 – short-term interest rates have been steadily rising. This usually happens anyway as the business cycle comes to a close.

But what it tells you is that this particular business cycle was prolonged – by a lot – with the Fed artificially keeping short-term interest rates low, not by manipulating the benchmark federal funds rate, but through quantitative easing and then refinancing a vast horde of U.S. treasuries.

The U.S. is long overdue for a recession – it usually happens once every six to seven years and we’re 10 years out from the last one – and now the next one has finally appeared on the horizon. But this time, it appears to have been at a time of the Fed’s choosing. It could have started dumping U.S. treasuries and mortgage bonds months earlier, years earlier even, but instead it waited until after former President Barack Obama’s two terms of office had ended.

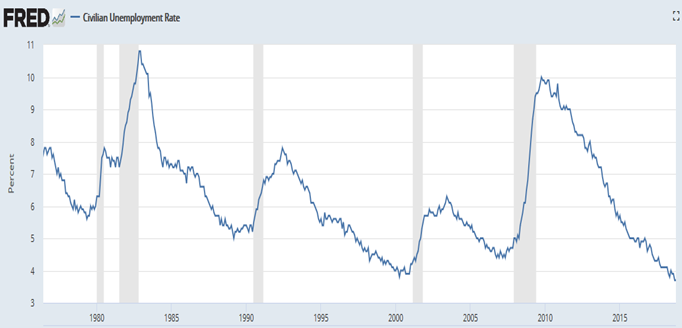

To be fair, throughout Obama’s tenure, U.S. labor market conditions were still recovering slowly with very sluggish economic growth. The Fed’s company line during that time was they wanted to get back to full employment before they normalized policy. And that didn’t happen until later in Obama’s term of office.

Now unemployment is at 3.8 percent. 4.8 million jobs have been created since Trump took office. This undoubtedly has played into the Fed’s comfort with hiking up rates, which are now in the 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent. It won’t take much for 10-year treasuries to get below that.

The Fed seems to be aware of where they are in the cycle. Starting in May, the Fed will go from dumping $30 billion of treasuries a month to $15 billion, and then in October down to nothing, and then further mortgage bond sales will then be offset by treasuries purchases. This will set the stage for a drop in short-term interest rates and a widening of the 10-year-3-month and 10-year-2-year spreads.

It knows the rates are at the inversion point, and so is already planning ahead for future rate cuts as we get closer to the recession when short rates begin dropping again. The rate hikes provided enough room to ease when things start getting hairy.

Meaning the stopwatches start now. On average a recession ensues anywhere in a range from 8 months to 17 months after the 10-year-3-month inverts – with an average of 13 months – data going back to 1981 suggests. So, anywhere from Dec. 2019 to Nov. 2020, you might expect to see unemployment rising substantially, right in the heart of the 2020 presidential race.

On the other hand, the 10-year-2-year has not inverted just yet and has a longer average period until a recession occurs after the initial inversion of 16 months. Assuming such an inversion happened soon, that might mean a recession might be just beginning in Oct. 2020. But if it doesn’t happen soon, it’s worth noting that there hasn’t been a recession in modern history without such an inversion.

Then there’s unemployment. After peak employment is reached for the first time in the business cycle, recessions come about an average of 11 months later, although the longest period measured in recent history was 16 months.

Point is, if the Fed had begun dumping treasuries and mortgage bonds in 2016, 2015 or earlier, the next recession might have already happened. Was it timed to forestall any new recession prior to 2016, which would have portended badly for the incumbent Democrat party?

And why did it wait until 2017 to beginning drawing down bonds? Just saying. If the Fed was trying to cause a recession right around the same time as Trump’s 2020 reelection bid, it probably could not have been timed its bond selloff and move off of zero-percent interest rates any better.

– – –

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.