by Brandon J. Weichert

Dick Cheney doesn’t have a heart. That, at least, is the intended conclusion one is supposed to draw from the recent Dick Cheney biopic, “Vice,” starring Christian Bale. In “Vice,” audiences are subjected to a torrent of subliminal messages suggesting Dick Cheney is an abnormal human being; a political Svengali, worshiping at the blood-stained altar of power. Everything Cheney did, so the story goes, was predicated upon the assumption of absolute power for power’s sake.

Whatever may be the legitimate criticisms about Dick Cheney, no one should believe such an inane leftist caricature any more than one should believe the grotesque false narrative that the elites today have about Trump. In both cases, these two very different men are far more complex than the tidy elite narratives would have it. “Vice” ultimately is a work a fiction. Yes, it includes real names and comprises actual bits of the real life experiences of the people portrayed in the film, but as a substantive contribution to understanding one of the most misunderstood political figures in American history, the film falls flat.

“Vice” is the latest a string of recent dramas produced by the notorious comedy director and writer, Adam McKay. From a cinematic point of view, the film is marvelous. Noted method actor, Christian Bale, becomes inseparable from the real-life Cheney, in terms of his dour demeanor, as well as Bale’s capture of Cheney’s voice and his size (Cheney was notoriously accused of having the disposition of an undertaker). Bale’s physical resemblance in the film is uncanny. Naturally, the film has the lion’s share of Academy Award nominations this season and, compared to its competition, it deserves the praise heaped upon it for the performances alone.

Cinematically, the film is incredible. For instance, when Cheney’s presidential bid in 1996 fizzles prematurely, the film ends—with credits rolling and exit music cued—for several minutes. Fellow moviegoers in the theater where I watched the film were entirely perplexed. Then, suddenly, the film returns to its normal pace. It was funny and jarring all at once (which was the point of the movie).

At another point, as if to fill in historical blank spaces, Cheney’s fateful decision to present himself as George W. Bush’s running mate in 2000 is made after he and Lynne Cheney (Amy Adams) share a bizarre, sexually-charged scene in which they recite Shakespeare to each other on their plush, king-sized bed. Not to insult the former vice-president or his highly intelligent wife, but I doubt either of them knows Shakespeare so well that they would have entered into a creepy, sexualized soliloquy of Shakespearean dialogue while deciding whether they should join Bush’s presidential ticket.

“Vice” is also quite different from Adam McKay’s other recent drama: “The Big Short.” Whereas “The Big Short” was a tightly-woven narrative, from the beginning, “Vice” is a hodgepodge of manic and visceral vignettes. From its very opening scene—that of a young Dick Cheney driving drunk on an isolated road in rural Wyoming, interspersed with scenes of a much-older Cheney being whisked out of his office in the Old Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C. and into a bunker beneath the White House on 9/11, the viewer is almost assaulted by the constant, jarring visual narrative.

From the start, the film’s narrator (Jesse Plemmons of “Friday Night Lights” and “Breaking Bad” fame) acknowledges that little is known about Cheney’s life (other than what the Cheneys want us to know about it). Oddly enough, biopics traditionally are meant to enlighten audiences about their subject matter while still providing dramatic subtext. For instance, the film “Amadeus” does both very well (it illustrates the chaotic, yet brilliant nature of Mozart compared to the little-known, though insanely jealous rival composer of the time, Salieri). “Amadeus” provides insight that otherwise was lacking. “Vice” does nothing like that. It is entirely character-driven. From an acting perspective, this is a good thing: the film has a powerful cast that shines in each scene. But, the film’s experimental nature can be confusing and its story convoluted (to say nothing of its accuracy). And, of course, all of this is compounded by the highly politicized nature of the film.

From the outset of the film, it is taken for granted that Dick Cheney is an evil man out to do evil things. Lacking all belief or conviction, it is suggested that Cheney’s fundamental nature is of one who merely yearns for power. He skulks about the White House, either as an aide to then-White House Chief of Staff Donald Rumsfeld or as the vice-president of the United States, driven only by his desire for more power. It is also taken as a given that, as a Republican, he is greedy and selfish (added to these assumptions are strange and gratuitous jabs at Donald Trump and his illegal immigration policies). Why is Cheney this way? What is the case for it? Little information is given so one is not persuaded by the film, he is simply assaulted by the assumption.

Yet, analyzing even the most critical books about Dick Cheney, one comes to see—in the formulation of noted Cheney critic, The Washington Post’s Dana Priest—the former vice-president became “evangelical” about fighting terrorism following the 9/11 attacks.

Why would one who was merely driven by the mindless, beastly acquisition of power concern himself with protecting other people? In every scene, there is the implicit assumption that few members of the audience would view Cheney as sympathetic or even normal. He is the villain; the Iago. The film’s only quest is to document that villainy as frenetically as possible. This is the film’s most serious error. Dick Cheney is a flawed human being, as are all human beings. But Cheney’s life has been consequential and his importance to American history transcends the fact that he became the “shadow president” during the first term of George W. Bush’s quixotic presidency.

So much time is expended grinding in these assumed flaws in Cheney’s character however, that his actual failures are barely noted. There is no mention, for instance, of his claims that “deficits don’t matter” or his assurances that American forces would, in fact, “be greeted as liberators” in Iraq. Indeed, there is no attempt at substantive criticism of Dick Cheney because there is no capacity on the part of the film’s makers, it seems, to come to grip with the reality that Cheney is not an evil man. This makes his failures more, not less compelling.

He is a patriot in the truest sense. Cheney is also a loving father and committed husband. The film does throw him a bone here, notably (if predictably) when his youngest daughter comes out as a lesbian. Yet, the film goes to great lengths (as every modern biopic about Republican leaders does) to portray his wife, Lynne, as a power-mad kingmaker to the “shadow president.” More than anything, the film does a terrible disservice to her.

Cheney’s problem wasn’t that he possessed a gaping hole for a heart (and the film literally depicts this in the end) who, like some Borg drone, assimilates the hearts of other less-fortunate Americans (such as that of Jesse Plemmons’ narrator and heart donor character). His problem was that he over-committed. Far from being devoid of ideology or a heart, Cheney likely put too much faith in the idea that he and his cohorts were doing the right thing in response to the terror threat coming from the Middle East. The film totally misses this. Instead of grappling with the true and deeply flawed nature of a fundamentally decent person who was wrong on certain issues, it clumsily and heavy-handedly strains itself in order to make a Left-wing political statement. Thus, as a biopic, “Vice” is a failure: it does not elaborate on an interesting though little understood subject and, in fact, it contributes to that subject’s continued misrepresentation.

Of course, you should form your own opinion. I do recommend this film for the sheer potency of the performances of those in the film and for the experimental nature of the movie. But, don’t go expecting an objective discourse on the facts.

Like so many other films today, it’s all leftism all the time.

– – –

Brandon J. Weichert is a geopolitical analyst who manages The Weichert Report. He is a contributing editor at American Greatness and a contributor at The American Spectator . His writings on national security have appeared in Real Clear Politics and he has been featured on the BBC and CBS News. Brandon is an associate producer for “America First with Sebastian Gorka” and is a former congressional staffer who is currently working on his doctorate in international relations.

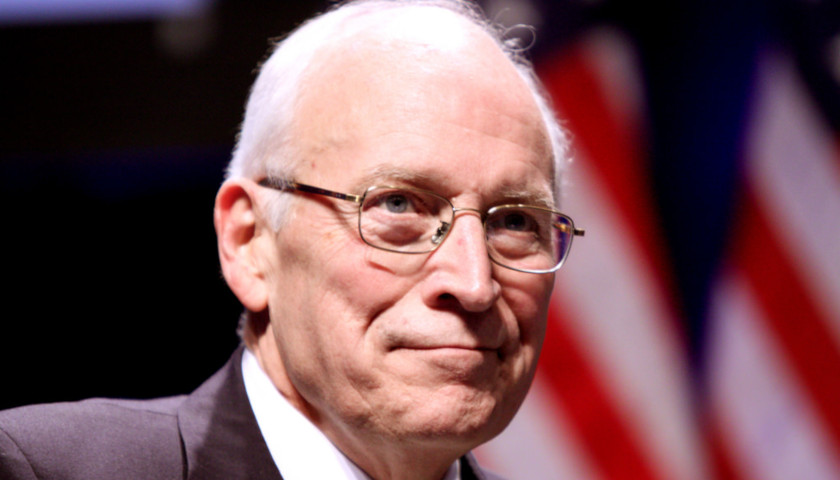

Photo “Dick Cheney” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0.