This is the second story in an eight-part series on the Ohio Public Health Advisory System

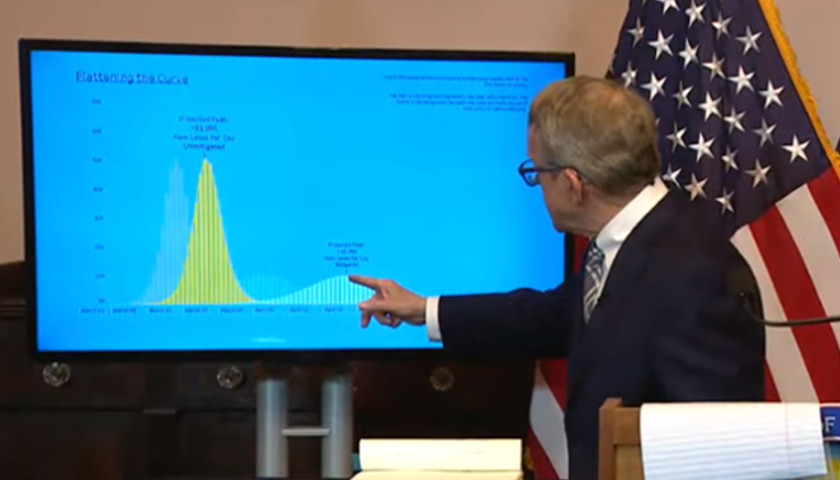

Early in the battle with COVID Ohioans were implored to heed recommended measures from Republican Governor Mike DeWine and Ohio Department of Health Director Amy Acton to “flatten the curve and ramp hospital capacity.”

Experts displayed epidemiological curves showing as many as 62,000 new cases a day, while county and local health departments received epidemiological reports highlighting the projected death toll on each age group within the locale or county.

The Ohio Department of Health projected COVID would infect 30% to 70% of Ohioans, consequently killing 35,000 to 80,000 Buckeyes.

A video produced by a Bluffton College professor blew up on social media and the message was clear – take the virus seriously or prepare to deal with more critically sick patients than our hospitals can handle.

Daily 2 o’clock pressers routinely covered cases, hospitalizations, ICU visits and deaths. As it became apparent initial projections were exponentially overstated, Ohioans began to question a one-size-fits-all policy to manage COVID.

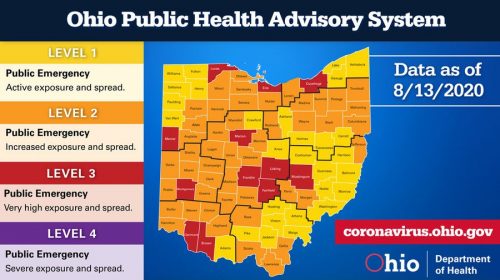

On July 2 Governor DeWine introduced the Ohio Public Health Advisory System (OPHAS) – a color-coded map that assigned a threat level color to each of Ohio’s 88 counties. The system is supposed to be an early warning indicator of COVID spread by county for use by businesses, communities and local governments.

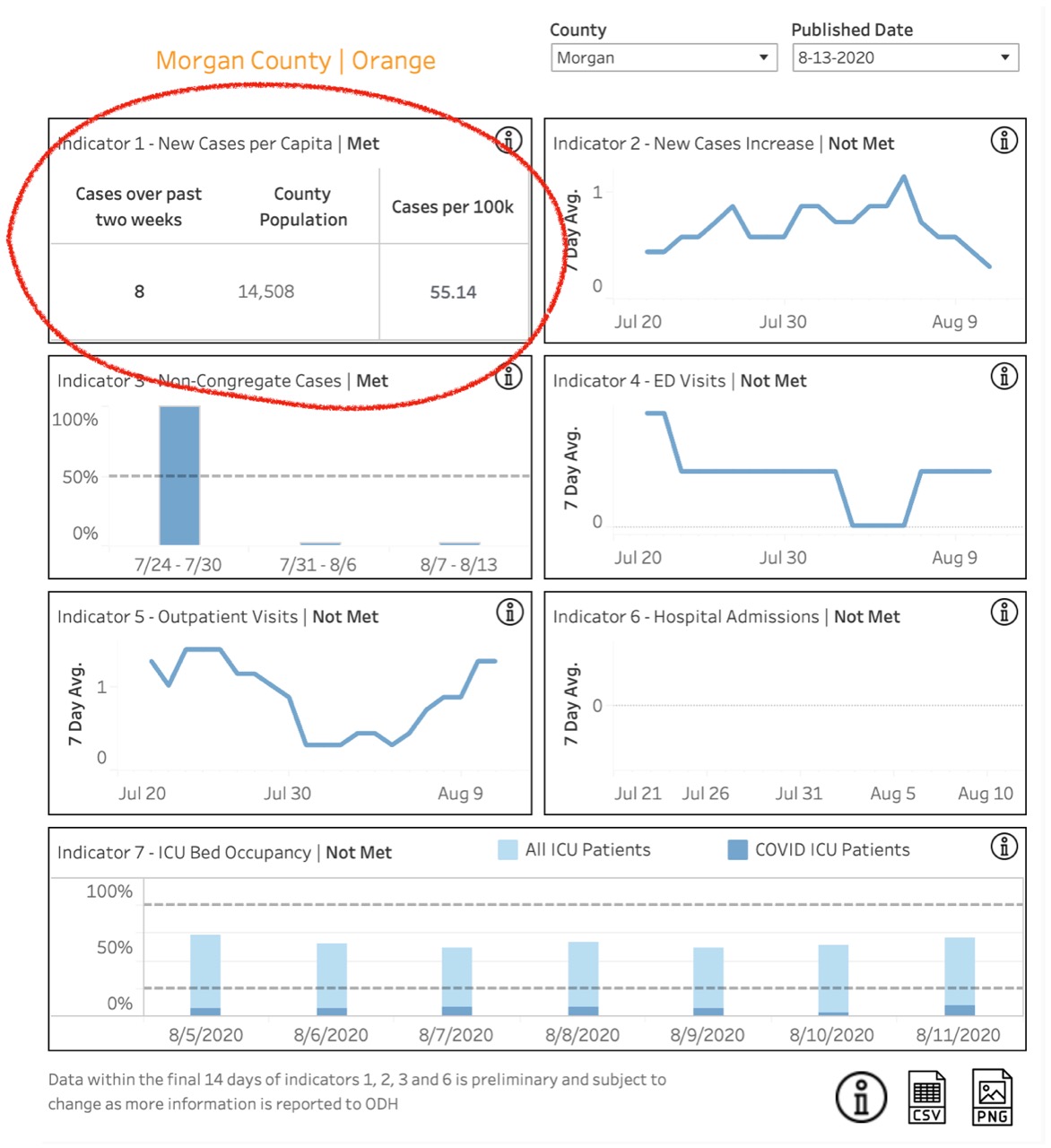

The threat level is the result of county’s grade on seven indicators: case data (indicators 1-2), symptom data (indicators 4-5), hospitalization data (indicators 6-7). A county in yellow triggers 0-1 indicators. A county in orange triggers 2-3 indicators. A county in red triggers 4-5 indicators. A county in purple triggers 6-7 indicators.

The threat level is the result of county’s grade on seven indicators: case data (indicators 1-2), symptom data (indicators 4-5), hospitalization data (indicators 6-7). A county in yellow triggers 0-1 indicators. A county in orange triggers 2-3 indicators. A county in red triggers 4-5 indicators. A county in purple triggers 6-7 indicators.

The advisory system was supposed to push down decision making to local levels. However, Governor DeWine issued a statewide mask mandate, despite – at the time – a decrease in new cases in high risk counties.

Although a system for predicting and combatting a virus would be difficult to perfect, the broad analysis of cases, symptoms and hospital data is intended to bring wide visibility as a predictive measure.

The advisory system relies more than 40% on tests, a near 30% on symptoms and another nearly 30% on hospitalizations and ICU occupancy.

Indicator 1: New Cases Per Capita

The new cases per capita indicator is triggered if greater than 50 new cases are reported per 100,000 people over a two-week period.

New cases include confirmed cases and probable cases. Probable cases do not contain only confirmed COVID cases and lack certainty about viral prevalence.

New cases include confirmed cases and probable cases. Probable cases do not contain only confirmed COVID cases and lack certainty about viral prevalence.

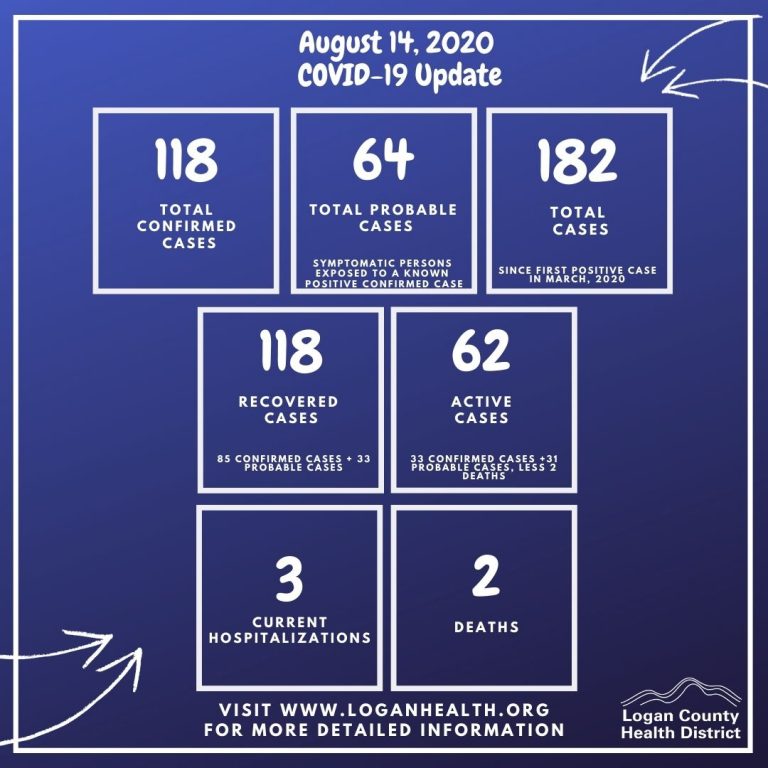

As of August 14, 35% of Logan County cases are probable – cases that do not have a conclusive laboratory result or are counted due to close contact with another laboratory confirmed positive case.

An increase of just a few cases is punitive for counties with smaller populations.

Morgan county has a population of 14,505. As reported on August 13, over a period of two weeks Morgan County reported 8 cases – when adjusted for per capita calculations, that equates to 55.14 cases per 100,000 people, which triggers the new cases per capita indicator.

Morgan county has a population of 14,505. As reported on August 13, over a period of two weeks Morgan County reported 8 cases – when adjusted for per capita calculations, that equates to 55.14 cases per 100,000 people, which triggers the new cases per capita indicator.

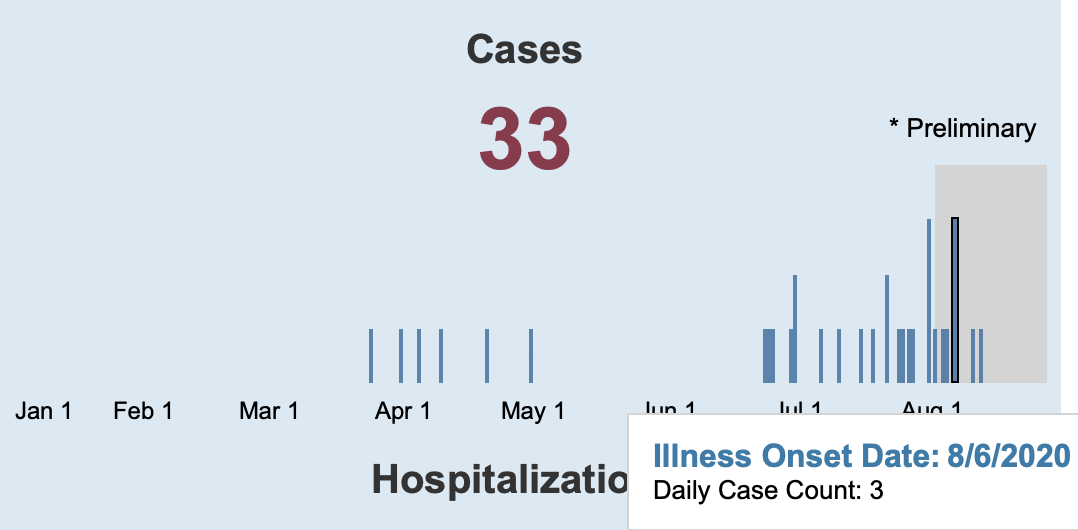

Morgan County has had 33 cases since March with zero hospitalizations and zero deaths, yet was moved to code orange – the OPHAS indicates Morgan county is a community with “increased exposure and spread” and should “exercise [a] high degree of caution.”

False test results are problematic for counties when measuring new cases per capita. False positives can be enough to push a county into a higher threat level.

False positive results are problematic for individuals, too.

On August 6 Governor DeWine was on his way to Cleveland to meet President Donald J. Trump when he was administered a rapid-return antigen test that was positive. Later in the day DeWine took a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to overturn the false positive.

Dr. Amy Edwards, associate medical director for infection at University Hospitals in Cleveland, commented on DeWine’s false positive during an interview with Cleveland19 saying “antigen tests are notoriously plagued with issues of accuracy.”

Ironically, just a few days earlier Governor DeWine announced his intent to partner with a multistate consortium to purchase from The Rockefeller Foundation 500,000 antigen tests for use in upcoming months.

Since that statement, Governor DeWine’s Press Secretary Dan Tierney talked with The Ohio Star and walked-back the Governor’s comments, saying the agreement is still in negotiation and may include other test types.

Since that statement, Governor DeWine’s Press Secretary Dan Tierney talked with The Ohio Star and walked-back the Governor’s comments, saying the agreement is still in negotiation and may include other test types.

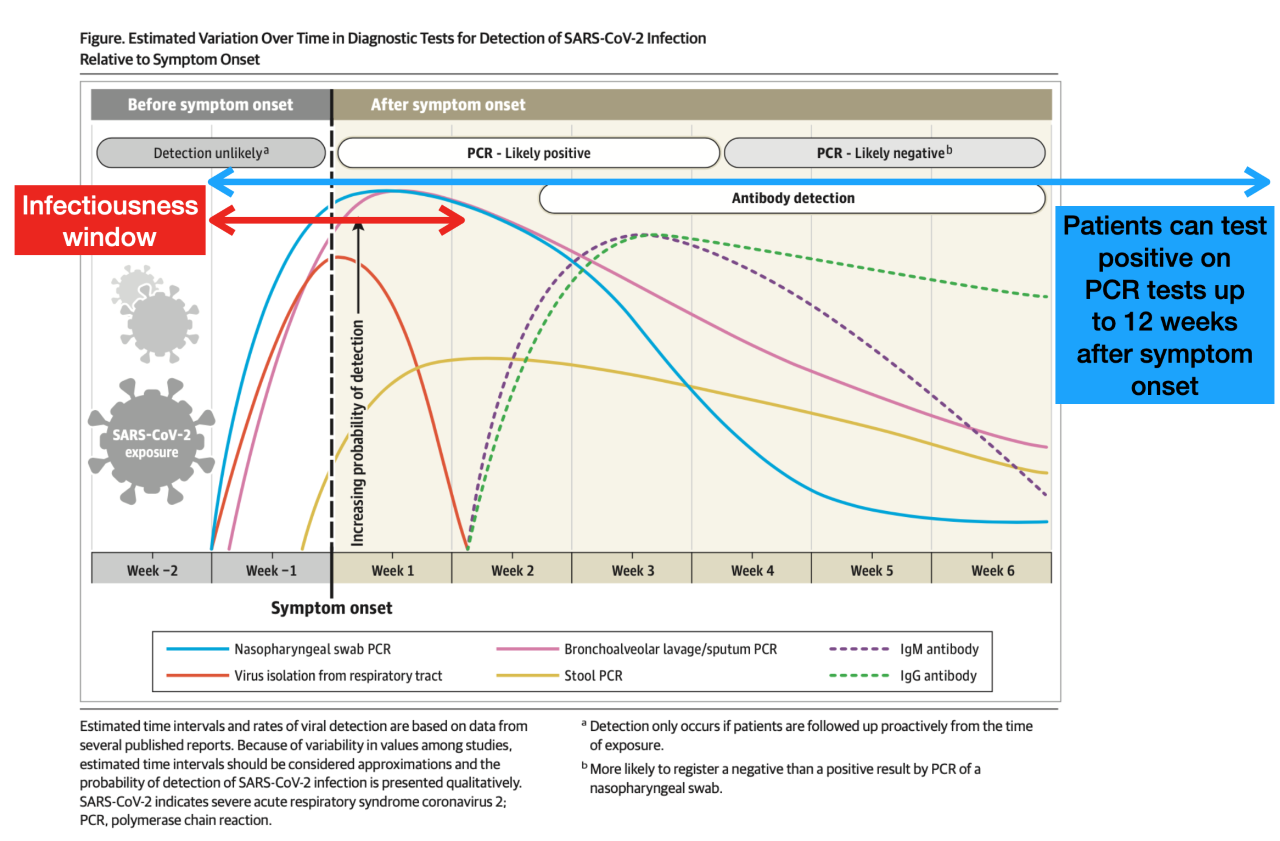

PCR tests are deemed gold standard. However, even PCR tests have glitches. The Journal of American Medical Association, a peer reviewed publication, found PCR tests can render positive results for up to 12 weeks, almost 10 weeks past infectiousness – beyond the window of time when the virus can be transmitted.

Unlike DeWine, other Ohioans do not get an uncontested second opinion.

A Cincinnati mother who is not anonymous to The Star, but asked to remain nameless to readers for fear of backlash in the community (referred to next as Jane), discussed during a phone interview a false positive test her daughter (herein referred to as Mary) received when tested at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Mary was a soon-to-be college freshman gearing up to attend an out of state school. Mary went on a road trip in mid-July to meet her roommate for the upcoming year at the roommate’s home in another state.

While there, Mary’s roommate received a call indicating she had been in contact with a COVID-positive friend during an Independence Day celebration. Consequently, Mary packed and headed back to Cincinnati – calling her parents on the return trip to inform them.

When she arrived home, Mary was met with caution – her family was masked and allowed her to go straight to her room where she would stay, honoring social distancing. Mary interacted with her family, from a distance, only a few times a day when her parents put meals outside her door and when Mary popped her head out to receive a forehead temperature check.

Mary was asymptomatic and feeling healthy, yet out of caution decided to get a test at the drive-up center at Children’s. That test returned negative. However, because of the exposure during her trip, she was advised to test again in a few days – right before her high school graduation party.

The second test was administered at Children’s but this time in the lab. This second test returned a positive result. Consequently, Jane cancelled Mary’s graduation party.

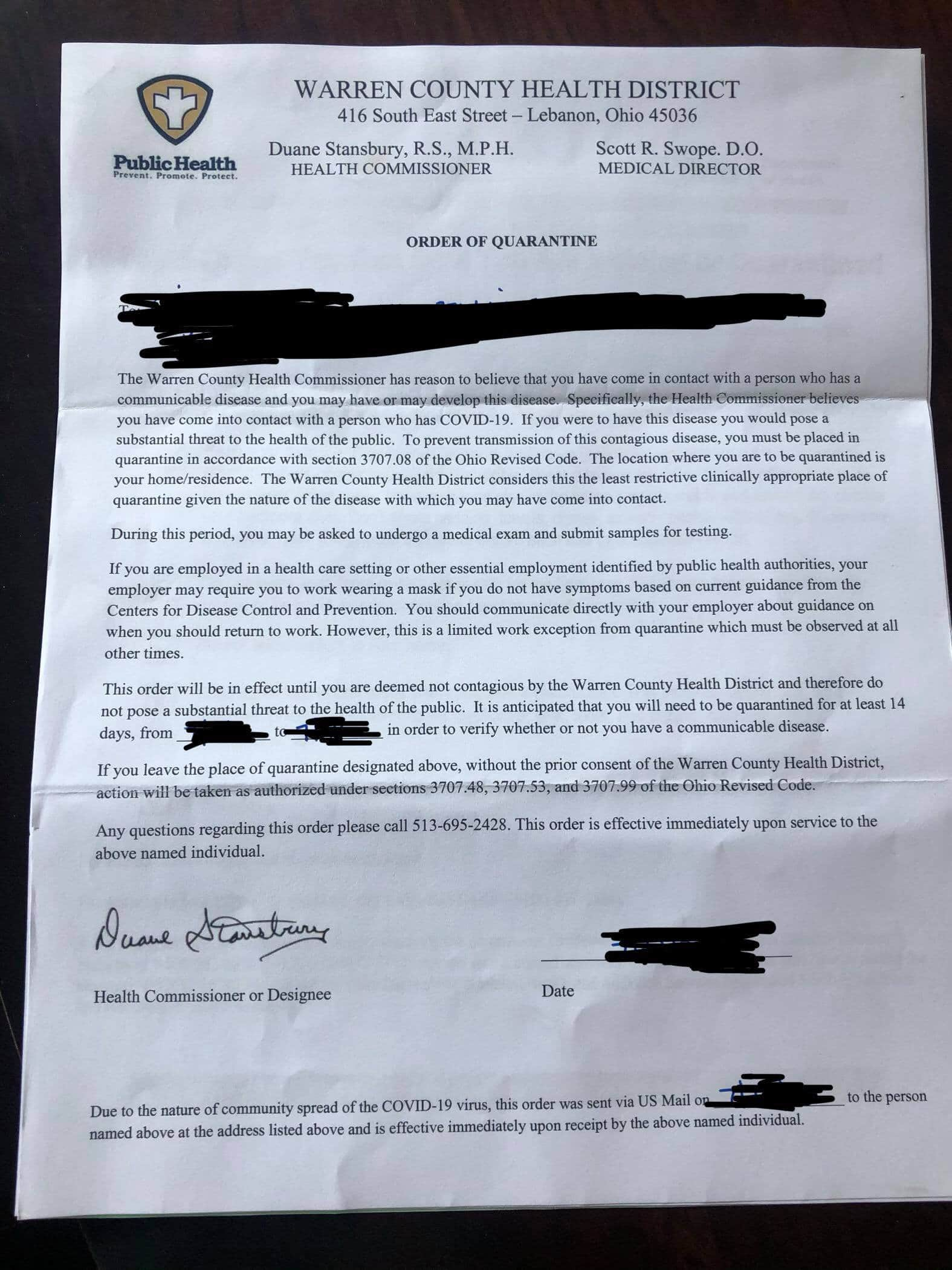

Two days later, Mary and Jane received quarantine letters, both containing instructions along with Ohio Revised Code sections to influence their compliance.

Still without symptoms, Jane called Children’s and demanded a third test – “I had to press the issue because the doctor didn’t want to do it.” The third test came back negative. Despite delivering two negative tests, the county health department still counted Mary’s positive test and monitored Mary and her family.

Mary’s first and third tests (both negative) were single step RT-PCR tests. Mary received indication that the test’s validation for use is “pending before the FDA.”

Mary’s second test (the positive) was a DiaSorin Molecular test with the following FDA disclaimer: “this test has not been validated for use in asymptomatic patients, and results should be viewed with caution.”

————–

Jack Windsor is Managing Editor and an Investigative Reporter at The Ohio Star. Windsor is also an Investigative Reporter at WMFD-TV. Follow Jack on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected]. Kathryn Huwig was a data and analysis contributor.