by Robert Romano

The U.S. economy got another dose of amazing news on Oct. 4 when the national unemployment rate dropped to a 50-year low of 3.5 percent.

Add to that, 6.1 million jobs have been created since President Donald Trump took office.

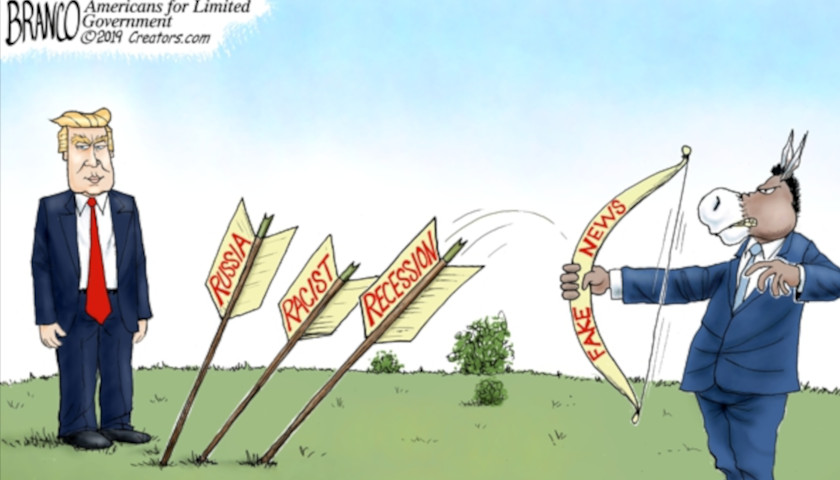

And that means Democrats hoping for a recession for the 2020 election to help oust Trump might be a little bit disappointed in the coming months.

What makes it even more significant is that when it was that low in 1969, the Vietnam War was still at its height more or less, with hundreds of thousands of working-age males overseas and hundreds of thousands more enlisted.

Granted there are still many deployments from the ongoing War on Terror in Afghanistan and elsewhere plus securing locations in Germany and South Korea and elsewhere but not nearly on the scale seen back then.

The point is, in relative peacetime—I say, relative—that’s a really low unemployment rate. Really, really low.

And with a new low realized in this cycle — the previous low was hit in April at 3.6 percent — any recession clock has now been reset. Once peak employment has been reached for the first time in a business cycle, a recession comes on average about 11 months later, although in recent history that period has been as long as 16 months.

And with a new low realized in this cycle — the previous low was hit in April at 3.6 percent — any recession clock has now been reset. Once peak employment has been reached for the first time in a business cycle, a recession comes on average about 11 months later, although in recent history that period has been as long as 16 months.

That might put any recession — assuming we’ve hit peak employment — anywhere from Aug. 2020 to Dec. 2020, probably too close to the election for anyone to notice or for it to turn up in the data.

But, you usually don’t know you’ve reached peak employment until after it has begun rising a bit. Many analysts probably would have bet in April that the jobless rate would not go any lower than 3.6 percent, but here we are, many months later and a new 50-year low at 3.5 percent.

Here’s the thing. Amid shifting demographics and surplus demand for labor, plus fewer high school dropouts and a greater percentage of the workforce finishing college, the unemployment rate can go even lower.

And if it does, that will mean that again, the recession countdown clock will have to be reset.

And if it does, that will mean that again, the recession countdown clock will have to be reset.

Further dashing Democrat hopes for an early recession, the 10-year, 2-year spread, after briefly inverting, uninverted last month to little fanfare or reporting.

Making matters worse for the Recessionistas, It may not have inverted far enough or stayed down long enough to bake a recession into the cake. Some terms and conditions may apply. It might have been a false signal.

Something similar happened in 1998 with a month-long, shallow inversion between the 10-year, 2-year that ultimately proved to be too early to predict the March 2001 recession.

Now that could all mean nothing and those two rates could invert again tomorrow or that brief inversion we saw was in fact a recession signals. Again, you really don’t get to find out until after the fact.

It’s as much guesswork as anything else. All we’re proving here is for every analysis suggesting that the data is predictive of a recession occurring soon, there are others that say it might not happen until later.

It’s as much guesswork as anything else. All we’re proving here is for every analysis suggesting that the data is predictive of a recession occurring soon, there are others that say it might not happen until later.

Which is the point. On the political side, every month that goes by and the Trump economy stays strong or even just delivers consistent numbers showing economic and job growth, it dispels fears by the American people that there was any danger to the economy — and voters are going to take that into consideration in 2020, no question. They ought to.

I’d say it can’t get any better than this, but we already know it can.

Democrats’ problem as 2020 approaches rapidly is that if they’re betting on events like a recession hitting, they’re running out of time. So while economic news remains good, it makes attempts at impeachment look even more politically motivated as voters start to wonder if the push to remove Trump before the election is because with the economy and labor markets so strong Democrats don’t think they can beat him at the ballot box.

– – –

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.

Photo by Americans for Limited Government.