by Deal Hudson

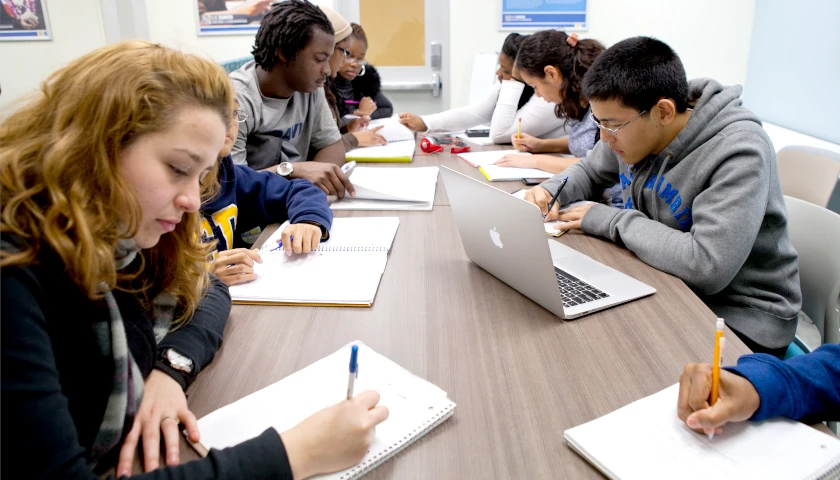

Those classics that are called the Great Books are most closely associated with Mortimer J. Adler and Robert Hutchins. When Hutchins became president of the University of Chicago in 1929, he hired Adler to teach philosophy in the law school and the psychology department. Upon arriving, Adler, rather brashly he admits, recommended to Hutchins a program of study for undergraduates using classic texts. Adler had taught in the General Honors program at Columbia University begun in 1921 by professor John Erskine. Hutchins asked him for a list of books to be read in such a program. When Hutchins saw the list, he told Adler that he had not encountered most of them during his student years at Oberlin College and Yale University. Hutchins later wrote that unless Adler “did something drastic he [Hutchins, referring to himself] would close his educational career a wholly uneducated man.” Hutchins remained president for 16 years before serving as chancellor until 1951, and the following year, they did something drastic.

In 1952, Adler and Hutchins published the Great Books of the Western World in 54 volumes. Adler and Hutchins included the 714 authors they considered most important to the development of Western Civilization. The influence of their Great Books movement on American culture for several decades was considerable and continues to this day.

Their selection of books from over a half-century ago has held up rather well. For example, I compared them to the 2007 list published by journalist and cultural critic J. Peder Zane. Zane asked 125 leading writers to list their favorite works of fiction. Zane found that the 20 most common titles listed by the writers were:

- Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy (1877)

- Madame Bovary, Gustav Flaubert (1856)

- War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy (1869)

- Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain (1884)

- Hamlet, William Shakespeare (1600)

- The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

- In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust (1913-27)

- Stories of Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)

- Middlemarch, George Eliot (1871-72)

- Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes (1602, 1615)

- Moby Dick, Herman Melville (1851)

- Great Expectations, Charles Dickens (1860-61)

- Ulysses, James Joyce (1922)

- The Odyssey, Homer (9th century B.C.)

- Dubliners, James Joyce (1916)

- Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866)

- King Lear, William Shakespeare (1605)

- Emma, Jane Austen (1816)

- One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1967)

Adler and Hutchins included all these books except for the two by Nabokov and Marquez. In spite of their absence, modernity is well-represented in the Great Books by Bertolt Brecht, Samuel Beckett, and William Faulkner, among others.

Zane’s survey refutes the claim that lists of “greats” reflect only the opinions of middle-aged white men. The 120 writers interviewed by Zane would satisfy any diversity requirement. If someone asked the same number of philosophers, historians, or scientists about their favorite books, I predict the results would have been much the same: the new list would contain a majority of acknowledged classics with the addition of some more recent and specialist books.

Poetry

Classic poetry is well-represented in the Great Books – Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, and Eliot are there, plus others. But poetry read in the context of the Great Books can be approached as a source of ideas or as another link in the history of ideas. This is a mistake. Poetic language is a linguistic fusion of form and content, a creation that resists being plucked for concepts to fill in the philosopher’s timeline.

Someone might object to the continued relevance of poetry because no one reads poetry anymore except when assigned in a classroom. However, poet and critic Dana Gioia reports that poetry has undergone a cultural revival outside of the academy, where poets have often found a steady paycheck. Gioia calls it “a tale of two cities”; a new generation of poets is finding their voice in the real world:

They work as baristas, brewers, and bookstore clerks; they also work in business, medicine, and the law. Technology has made it possible to publish books without institutional or commercial support. Social media connects people more effectively than any faculty lounge. An online journal requires nothing but time. Any person with an iPhone and a laptop can produce a professional poetry video. Any bookstore, library, cafe, or gallery can host a poetry reading.

A 2017 study by the National Endowment of the Arts shows that 11.2 percent of American adults, 28 million people in the United States, still read poetry.7 But young adults, in particular, ages 18 to 24, are leading the return, with 17.5 percent reporting regular poetry reading, a doubling of interest since the last such study in 2012 (8.2 percent). Regardless of how many poetry books you have on your shelves, or how many you see at your local bookstore, poetry thrives. Human beings need to sing, to express themselves beyond the limits of discursive reasoning.

Like music, poetic language engages the reader at an emotional level that goes untouched by philosophical reasoning. Before the philosophers, it was Homer who instructed the Greeks about gods and heroes. But his epics were sung, not read. The Iliad and Odyssey were sung by bards who held them in memory for a thousand years before they were written down.

Wilfred Owen

If someone assigned me the job of introducing poetry to neophytes, one of the first books I would assign my students is the poetry of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918). His life was short because he went to war, dying exactly one week before the end of World War I. After college, Owen went to Paris where he taught both English and French. He witnessed the beginning of the war and two years later returned to England where he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. His experience in battle is recorded in the poetry which was inspired, in part, by time spent in a hospital with the already-established poet Siegfried Sassoon.

Owen could have stayed home but returned to the trenches where he died four months later. I’m amazed at what Owen wrote before turning 26. In “Disabled,” he writes about a soldier returned home without his legs, in a wheelchair, watching football from the sidelines:

About this time Town used to swing so gay

When glow-lamps budded in the light blue trees,

And girls glanced lovelier as the air grew dim,—

In the old times, before he threw away his knees.

Now he will never feel again how slim

Girls’ waists are, or how warm their subtle hands.

All of them touch him like some queer disease.

In “Strange Meeting,” Owen imagines a soldier jumping into a crater in no man’s land and finding the corpse of an enemy soldier staring at him: “By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell.” The live soldier addresses the dead one: “Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.” But the corpse interrupts:

“None,” said that other, “save the undone years,

The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world”

The glory of war as told by Homer, Virgil, Herodotus, Thucydides, and Caesar Augustus was read in school by soldiers on both sides of the trenches. What this soldier found instead was “the pity of war, the pity war distilled.” With his thoughts of glory extinguished by death, he imagines himself back in battle:

“Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels,

I would go up and wash them from sweet wells,

Even with truths that lie too deep for taint.

I would have poured my spirit without stint

But not through wounds; not on the cess of war.

Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were.

“I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now. . . .”

A spiritual sense pervades these lines: “I would have poured my spirit without stint.” The bloody “chariot-wheels,” a reference to Homer’s Iliad, are cleansed “from sweet wells,” like Jacob’s Well (John 4:5–6), a pilgrim site in the ancient city of Nablus for centuries. The dead soldier tells the one living, “I am the enemy you killed, my friend,” and then offers him his forgiveness with the words, “Let us sleep now.” At the end of this ghastly encounter, Owen concludes on a note of nobility and common cause.

Reading Owen answers our questions about what men experience in battle, how they are able to face death, and how they cope with the experience of battle. The best literature takes us to places and circumstances we can only vaguely imagine and gives us access into the interior lives of people we would otherwise never know.

Making Lists

An indispensable guide to classics is The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages by literary scholar Harold Bloom. He organizes his book around 26 select authors, including the poets Shakespeare, Dante, Chaucer, Milton, Goethe, Whitman, Dickinson, Neruda, and Pessoa. His appendices, however, include lists of other books he considers canonical catalogs by era – Theocratic, Aristocratic, Democratic, and Chaotic – and by country. Bloom’s book is one of the best sources I have found to help one become familiar with the names and works of important writers around the world, and he has published a remarkably helpful set of lists for the reader.

Although classic texts are included in some high school and college curricula, it’s the rare student who can deeply appreciate King Lear or Macbeth as a teenager or young adult. The worldly profundity of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary or Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence, for example, is lost on all but a few teenagers, as it was lost on me. Books like Moby Dick, The Scarlet Letter, and The Great Gatsby pose the same challenge. We want to introduce young readers to the classics, but, frankly, these, like many other classics, are books for grown-ups.

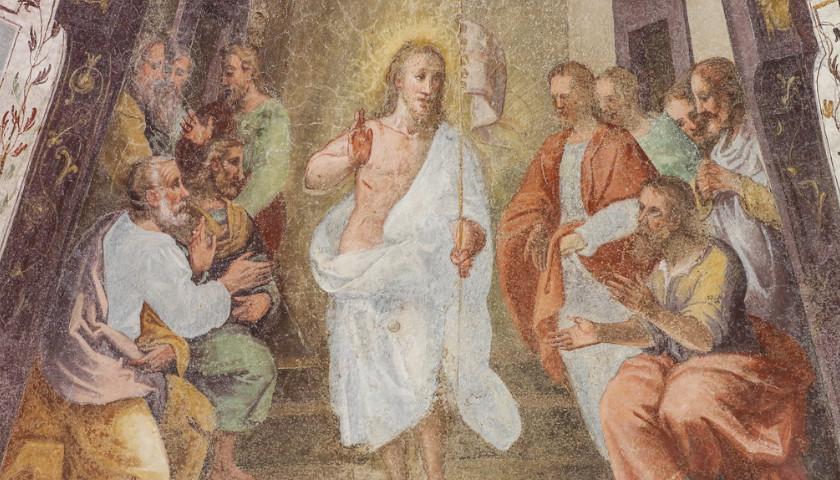

Philosophy and theology are central to any version of the Great Books—they address discursively those questions that have arisen in the lives of every person since Adam and Eve—meaning, morality, truth, justice, love, death, and eternity. Some philosophers and theologians, however, are more easily approached than others. There are always technical terms to master; for example, in Greek philosophy, the concept of Logos (“word,” “reason,” or “order”) which also plays a central role in Christianity: John 1:1 “In the beginning was the Word “ (λόγος, Logos). Every philosopher and theologian wrote in a historical tradition. Readers who pick up, for example, St. Thomas Aquinas will quickly see that he quotes from Scripture, Greek philosophers, Patristic Fathers, Roman writers, and Arab theologians. However, with some patience and access to online reference works, readers can acquire enough background knowledge to read Aquinas intelligently.

Later philosophers such as Kant, Hegel, and Heidegger are more difficult and test the patience of the nonspecialist. With the reader in mind, I discuss mainly the ancients and medievals in How to Keep From Losing Your Mind. These works are foundational for understanding Western civilization, and their influence is seen throughout the philosophy and theology that followed.

Greats and Classics

Greatness is measured in many ways, and any list of greats should be subject to criticism. I remember asking my then-college dean at a dinner party to name his top 10 novels, and he answered that “top 10 lists” were “nonsense.” A bit surprised, I replied, “But they are such great conversation starters!” He reluctantly agreed, but I had made a more important point than I realized at the time. Reliable lists are the answer to “Where do I go next?”

Let’s imagine a situation that I am sure has happened over and over: You’re listening to the car radio, flipping through channels; you hear a snatch of music that makes you stop, and you listen enthralled to the end. (This has happened to me more than a few times.) You wait to hear the announcer name the piece and the composer. You hear, “That was the ‘Violin Concerto’ of Samuel Barber.” “Who is Samuel Barber?” you ask yourself. What else did he write? Does anyone else write music that sounds like that? The Internet has made the answers very easy to find. You can read about Samuel Barber (1910-1981), see a list of his works and the best available recordings. Search further and you can find other composers who, like Barber, wrote music in a “late-Romantic” style. Good lists are invaluable to tell me what I don’t know.

Barber’s “Violin Concerto” inspires me to declare my description, not definition, of greatness. A book, a film, or a musical composition is great when you think to yourself, “I want to listen to all the music (or read the books and watch the movies) by this composer right away.” You may consider this too subjective, but I know I’m not alone in having that thought after reading Tolstoy, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Proust, Homer, Dickens, or Jane Austen; listening to Brahms, Dvorak, or Stravinsky; or watching the films of Kurosawa, Welles, or Eisenstein. As the late Harold Bloom put it, “I think that the self, in its quest to be free and solitary, ultimately reads with one aim only: to confront greatness.”

Let me clarify one thing: I am using the words great and classic as though they were interchangeable. There’s a distinction. Take, for example, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque. It’s a well-known classic novel about World War I. Remarque portrays the absurdity of the war for the soldiers on both sides who were expected to “go over the top” day after day. Remarque’s novel, published in German in 1928, had the good fortune of being translated into English the following year. Then the novel was made into an Oscar-winning 1930 film, “All Quiet on the Western Front,” directed by Lewis Milestone. Remarque’s book is still very readable, a classic novel about war and the First World War in particular.

However, when you compare Remarque’s novel to Magic Mountain (1924) by Thomas Mann, the limitations of Remarque’s novel are evident. Whereas Remarque explores the experience of life in the trenches of World War I, Mann’s scope is more universal, possessing layers of meaning about the shattering of European civilization as the result of the First World War. Magic Mountain depicts a turning point in Western culture through the fate of one man, Hans Castorp, who lives in a sanitorium for seven years trying to recover his health.

The most important criteria to use in determining greatness is the opinion of experts. Everyone has their personal favorites – arguing about why, say, one film is better than another is part of the delight of filmgoing. Experts, however, are qualified to make the hard call: to answer the question, where does this film or that book rank in comparison to the others? When I want to buy a new car, I ask the opinion of the mechanic who has been working on my cars for 20 years. Anyone who knows what is required to be an expert at anything will recognize the depth of knowledge needed to measure a book, a movie, a musical composition against all that has come before.

But it should be said, experts are not always right. Consider the list of Nobel Prize winners for literature. The first literature prize, given in 1901, went to the French poet René François Armand (Sully) Prudhomme (1839–1907) “in special recognition of his poetic composition, which gives evidence of lofty idealism, artistic perfection and a rare combination of the qualities of both heart and intellect.”

Prudhomme was a strange choice given the competition. In the previous decade, Dostoevsky had published Brothers Karamazov (1880). The next year, Henry James published A Portrait of a Lady followed by The Bostonians in 1896. Twain’s Huckleberry Finn was published in 1854, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1886, along with Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Ubervilles. In addition, Tolstoy published his “Kreutzer Sonata” in 1890. Searching for Prudhomme, I found only one of his books in English translation, the 1875 Les vaines tendresses.

Imagine being Sully Prudhomme when he received a letter from the Nobel committee and realizing he had beat out Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Twain, Stevenson, Hardy, and Henry James. He may have also thought of other writers active at the time: Guy de Maupassant, Emile Zola, Rudyard Kipling, W. B. Yeats, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, August Strindberg, Henrik Ibsen, and George Bernard Shaw. In the work of these “also-rans” we find inexhaustible stories of the human condition, universal in scope, all told with faultless command of language. All lists measuring greatness are subject to reconsideration—the truly greats remain on the list with the passing of centuries.

– – –

Deal W. Hudson is the publisher and editor of The Christian Review and author of “Onward Christian Soldiers: The Growing Political Power of Catholics and Evangelicals in the United States” (Simon and Schuster, 2008).

Endnotes

1) There were precursors to Adler and Hutchins’s Great Books. For example, in 1886, Sir John Lubbock published his list of “The Best Hundred Books, by the Best Judges” in the Pall Mall Gazette. See W. B. Carnochan, “Where Did Great Books Come From Anyway?” Stanford Humanities Review, vol. 6, 1995. Sir John’s list can be found here: Alex Johnson, “The Book List: Meet Sir John Lubbock, Godfather of the must-read list,” Independent, April 24, 2018.

2) Mortimer J. Alder, Philosopher At Large: An Intellectual Biography (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1977), 129.

3) Mortimer J. Adler and Robert Hutchins, Great Books of the Western World, 54 vols. (Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1952). A complete list of books can be found at “Adler’s Great Book List.”

4) I had the privilege of knowing and working with Dr. Adler later in his life, and I contributed several essays to his series of volumes, The Great Ideas Today.

5) J. Peder Zane, The Top Ten: Writers Pick Their Favorite Books (Boston: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007).

6) Dana Gioia, “Introduction,” Best American Poetry 2018 (New York: Scribner, 2018).

7) Sunil Iyengar, “Taking Note: Poetry Reading Is Up—Federal Survey Result,” June 7, 2018.

8) Wilfred Owen, The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen (New York: New Directions Publishing Company, 1993), 67.

9) The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen, 35.

10) Harold Bloom, The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages (New York: Riverhead Books, 1994), 485.

11) Hilton Tims, Erich Maria Remarque: The Last Romantic (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), 55–60, 69–72.

Yes, I have read some of those classical, mostly European authored, titles during both high school and undergraduate college some fifty years ago. Not all of us leftists are culturally ignorant of the authors and works you recommend. In fact, one can draw out ideas from them that can bolster the Left and rebut the Right. Huckleberry Finn also had a major anti-racist and anti-slavery theme despite Huck’s denial of being an abolitionist. Mark Twain the author was frequently an anti-war activist until his 1910 death.

We read some Marcel Proust and Andre’Gide works in high school French-language literature classes (as well as in college undergraduate courses). Many of these authors in their day came under attack more by the Right than by the Left. James Joyce had his run-ins with Victorian conservative prudes. The list goes on.

During most of my life, any attacks against these authors (while sometimes coming from the Left, originated chiefly from the Right)