by Anthony Cowden

In a recent article, John J. Mearsheimer traced America’s post-Cold War policy of engagement with China and the goals the U.S. hoped to achieve:

“Washington promoted investment in China and welcomed the country into the global trading system, thinking it would become a peace-loving democracy and a responsible stakeholder in a U.S.-led international order.”[1]

Mearsheimer goes on to document how spectacularly that strategy has backfired:

“Far from embracing liberal values at home and the status quo abroad, China grew more repressive and ambitious as it rose. Instead of fostering harmony between Beijing and Washington, engagement failed to forestall a rivalry and hastened the end of the so-called unipolar moment. Today, China and the United States are locked in what can only be called a new cold war—an intense security competition that touches on every dimension of their relationship. This rivalry will test U.S. policymakers more than the original Cold War did, as China is likely to be a more powerful competitor than the Soviet Union was in its prime. And this cold war is more likely to turn hot.”

To underscore the military challenge the U.S. would face in any hot war, a recent report by the Department of Defense estimates that the (PLAN) will have 460 ships by 2030, not including 80-some boats capable of launching anti-ship cruise missiles.[2] At less than 300 ships today, including the near-worthless LCS and the untested and under-armed DDG-1000, the U.S. Navy would have to expand by well over 50% in the next eight years to match the PLAN. Given that virtually all of the PLAN ships are dedicated to waters off the China coast, and the U.S. Navy has worldwide commitments, being able to deploy a competitive force to east Asia would require the U.S. Navy to grow by significantly more than that. That isn’t possible in the wildest of shipbuilding estimates.

And make no mistake, navies are critical in this contest. Any military operation against China would be a naval, air, and space/cyber battle involving relatively few ground forces. Given that U.S. budget politics require roughly equal funding between the Army, Navy, and Air Force, the Navy will never get the funding necessary to achieve even the Trump administration goal of 355 ships. Since it has been decades since the Navy has achieved any shipbuilding goal, whatever the Biden administration goal turns out to be will likely be unachievable as well.

There is simply no way the U.S. will be able to compete in a conventional military fight with China in East Asia in the near future – and maybe not today. But maybe the U.S. wouldn’t have to go it alone – maybe there’s another construct available to Liberal Internationalists, mutual defense treaty allies, could help turn the tide in a conventional fight with China? This would be Japan, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand in Asia. For various geopolitical, domestic political, and capability reasons, none of them can be counted on:

- Japan might very well be convinced to sit out a fight over, say, Taiwan, as they are close to and could suffer greatly from attacks by China – they may even restrict U.S. use of bases in Japan, further complicating U.S. military efforts.

- Thailand and the Philippines have no military capability to speak and would be in grave geographic danger of attack by China.

- Korea will not fight China unless China is involved in a war on the Korean peninsula, and maybe not even then.

- Australia and New Zealand have small armed forces, and New Zealand domestic politics might very well keep that country from aiding the U.S.

- For all of them, their mutual defense treaty is with the U.S., not Taiwan; an attack on Taiwan hardly obligates them to go to war with China on behalf of the U.S.[3]

So what strategy should the U.S. pursue to protect its interest regarding China? Broadly, the U.S. has three potential paths it could follow. In discussing these three national strategies, it is assumed that China does not implode from the enormous internal challenges it faces – demographic, financial, economic, etc. It cannot be assumed that such an implosion would have no negative effects abroad, especially economic, but exploring this alternative reality is beyond the scope of this article.

In his article Mearsheimer proposes the following strategy:

“…maintain formidable conventional forces in East Asia to persuade Beijing that a clash of arms would at best yield a Pyrrhic victory. … Furthermore, U.S. policymakers must constantly remind themselves—and Chinese leaders—about the ever-present possibility of nuclear escalation in wartime. … Washington can also establish clear rules for waging this security competition, such as agreements to avoid sea incidents or other accidental military clashes. If each side understands what crossing the other side’s redlines would mean, war becomes less likely.”

If the U.S. follows Mearsheimer’s prescription China can wait until it has overwhelming conventional military superiority and the U.S. is even deeper in debt, and then it will be able to take whatever hard power moves, military or economic, it wants to. China barely spends any of its GDP[4], compared to the U.S.[5], on defense, yet it already has a navy bigger than that of the U.S. As noted above, there is no way the U.S. can afford to keep up with the size of China’s conventional forces; and since the U.S. refuses to raise taxes to pay for the government goods and services it buys, the U.S. will be both broke and outmatched.

With this strategy, if the U.S. attempts to counter China militarily, outnumbered at sea, in the air, and in space/cyberspace, the U.S. will be defeated conventionally. At this point, the U.S. might consider using nuclear weapons to turn the tide, inviting Armageddon in what will be correctly perceived by the international community as a vain and last-ditch attempt to cling to superpower status. Hopefully, saner heads will prevail, and the U.S. will have to concede defeat – at which point its fall from superpower status, combined with crushing debt no longer underwritten by international investors, would be complete: the value of the U.S. dollar would plummet, interest rates on new U.S. debt would skyrocket, the national economy would implode, and our time as a superpower will come to an inglorious end. And given the recent Insurrection, it is difficult to see how the U.S. survives this shock politically.

Alternatively, the U.S. could pursue a strategy of Neo-Isolationism. Neo-Isolationism calls for the U.S. to strictly define its national interests, significantly reduce its foreign entanglements, reduce its military expenditures, and rely on its nuclear arsenal to protect its existential interests. In other words, from a security standpoint, withdraw from the world; in the face of superior Chinese conventional military power, we wouldn’t be in any position to fulfill our security commitments to any Asian ally anyway.

A Neo-Isolationist strategy would be a gradual economic dis-engagement from China: China has not been a responsible international partner and should not continue to enrich them. This would certainly have adverse effects on the U.S. economy but would hurt China even more. And reduced expenditures on defense might allow the U.S. to underwrite the economic pain from dis-engagement from China and possibly invest in domestic priorities.

The third path involves the U.S. declaring economic war on China. This would involve increasing tariffs across the board to punitive levels while defining specific systemic changes China must agree to: intellectual property protection, opening markets, human rights improvements, climate change mitigation, etc. This would have a devastating effect on the U.S. and broader world economy, but it would pose an existential threat to China – and in the long run, it might be the only way for the U.S. to retain its relative power position in the world.

So, three choices, none of which are particularly palatable:

- Status Quo Until Destruction,

- Withdraw Inward, and

- Cut ‘Em Off.

The Status Quo Until Destruction strategy sees the U.S. humbled militarily and its economy destroyed, likely for generations, and poses an existential threat to the U.S. political system.

Withdraw Inward involves some short to mid-term economic pain, depending on how dis-engaging with China is managed, and a lot of angst amongst our allies and partners around the world, but the U.S. would eventually muddle through, but as a much-reduced world power by every measure.[6]

The Cut ‘Em Off strategy would involve significant short to mid-term economic pain for the U.S. and the world economy, and as China faces potentially existential economic and societal challenges, she might lash out violently.

So how likely is the U.S. to pursue one of these strategies?

Given the partisan political reality that exists in the U.S. today, it is hard to see how either of the last two strategies could be pursued: they both require significant cross-party agreement and cooperation to implement, not to mention a national public consensus as to the challenge and the remedy.

That leaves us with Status Quo Until Destruction. As its name implies, it doesn’t require political consensus, leadership, or national will – we’re on this path already. It would take a significant national change to get us off this path, and that just isn’t going to happen.

Unless China implodes for some reason, the Status Quo Until Destruction strategy will define our national future, and the outcome will be dire.

This article has painted a picture using a broad brush, and nothing is as hard or uncertain as predicting the future. Status Quo Until Destruction, for example, could have an entirely different outcome if one assumes China’s rise to regional hegemon with global power projection capabilities poses no strategic threat to its neighbors or U.S. interests. Get this wrong, however, and realism can be a real bummer for those nations whose pecking order in the international community changes radically: the U.S. saw its fortunes skyrocket at the end of WWII as it possessed the only undamaged major economy in the world; competition with China could see an opposite reality…

– – –

Anthony Cowden is the Managing Director of Stari Consulting Services and co-author of Fighting the Fleet: Operational Art and Modern Fleet Combat.

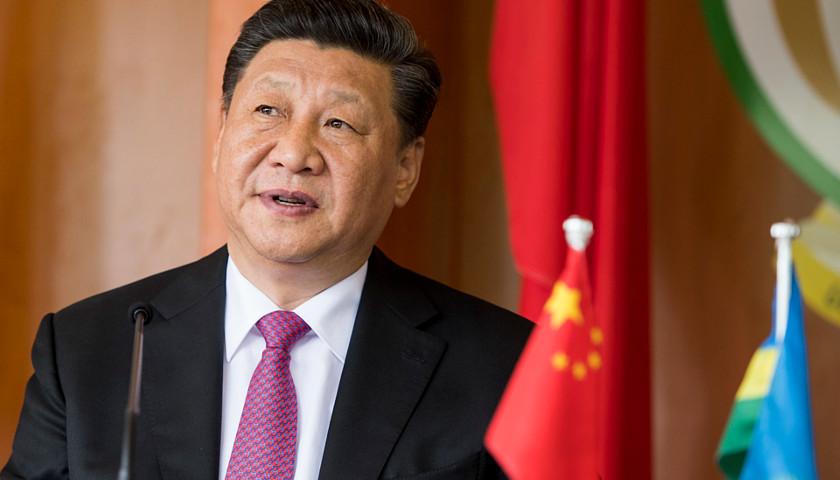

Photo “Xi Jinping” by Press Service of the President of the Russian Federation / Roman Kubanskiy CC BY 4.0.

Sounds like nobody is much interested in fighting China who actually live around them. Let them have Formosa. Why would on kid from Kansas of Vermont be sent to fight a war that even the locals don’t care to be in.