by James D. Agresti

“For the children we can save,” declared President Biden on June 2, “we should reinstate the assault weapons ban and high-capacity magazines that we passed in 1994.” To support this claim, Biden alleged:

And in the 10 years it was law, mass shootings went down. But after Republicans let the law expire in 2004 and those weapons were allowed to be sold again, mass shootings tripled. Those are the facts.

In reality, Biden is confusing terms and distorting data to paint a picture that is opposed to the facts. Such facts include but are not limited to the following:

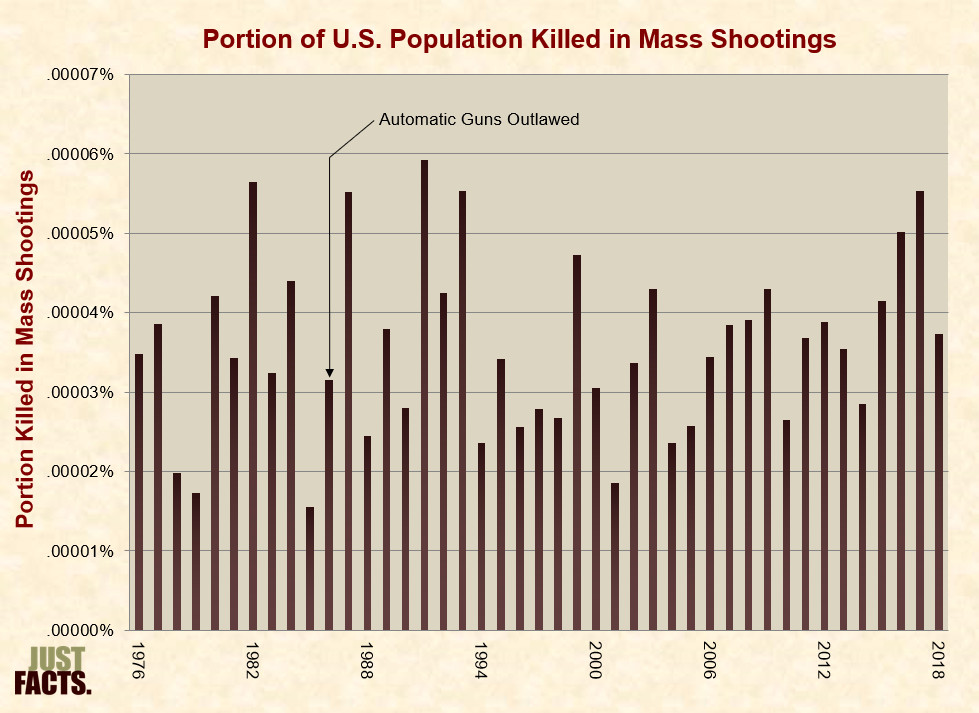

- The number of people killed in mass shootings didn’t decline even after the 1986 federal ban on automatic guns, which are more capable of mass murder than the guns Biden wants to ban.

- The terms “assault weapons” and “high-capacity magazines” are misleading and refer to common weapons used by citizens for hunting and home defense.

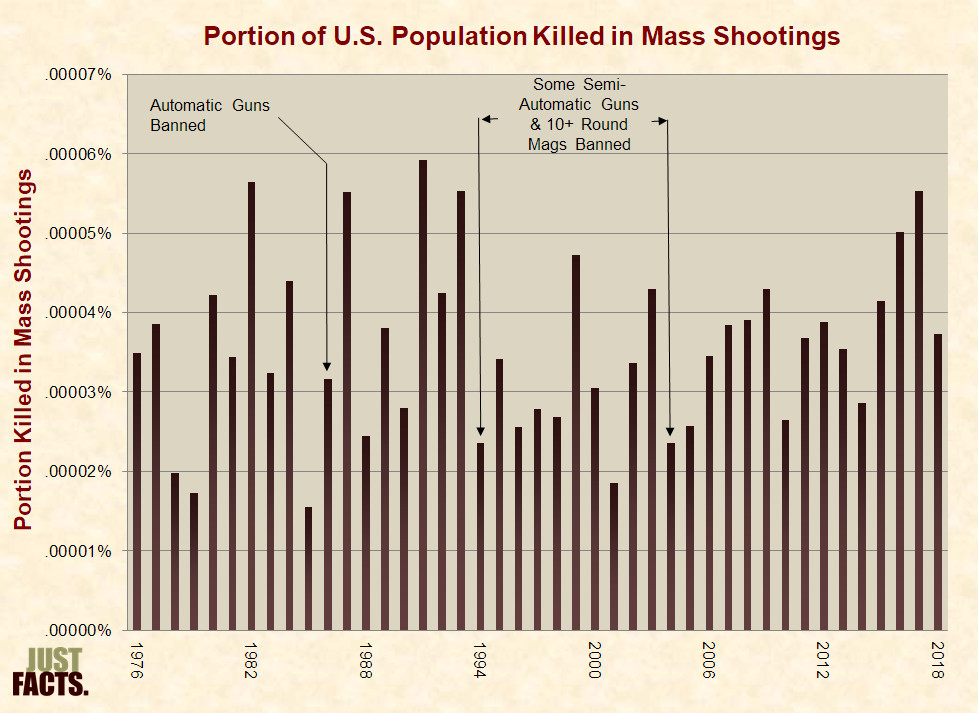

- Before, during, and after the 1994 law cited by Biden, the portion of the U.S. population killed in mass shootings barely budged, and the slight changes are better explained by other factors.

Automatic Firearms Have Been Banned Since 1986

Eight years before the “assault weapons” ban referenced by Biden, Congress passed and President Reagan signed a 1986 law which made it unlawful for civilians to “transfer or possess a machinegun.” Under federal law, the term “machinegun” means “any weapon” that can fire “more than one shot” with “a single function of the trigger.” Thus, the ban includes all types of automatic firearms, including machine guns, submachine guns, and assault rifles. These are the types of guns commonly used by armed forces.

The 1986 ban, which is still in effect, has an exception for guns legally owned before the law was enacted, but because automatic firearms have been heavily regulated since 1934, less than 4 million are currently owned by civilians. The relative rarity and strict regulation of these weapons is highlighted by a 2016 U.S. Department of Justice study which found “no evidence that” any owner of an automatic gun was convicted of using one to commit a crime from 2006 through 2014.

The primary purpose of the 1986 law was to reduce mass shooting deaths by limiting the availability of weapons with rapid rates of fire. As explained in the book Military Technology, “A machine gunner’s weapon fired hundreds of bullets each minute. He could point the weapon in the general direction of his enemy and fire. Even poorly-trained shooters could hit their targets. Automatic weapons made war a far more deadly business.”

Nevertheless, the portion of the U.S. population killed in mass shootings (defined in academic literature as those in which four or more people are killed), didn’t decline in the wake of the law:

Semi-Automatic “Assault Weapons” Were Banned From 1994–2004

Less than a decade after banning automatic weapons, Congress passed and President Clinton signed a 1994 law which made it illegal to “manufacture, transfer, or possess a semiautomatic assault weapon.” These guns often look like military firearms and share some characteristics with them (like detachable magazines and pistol grips), but they lack their defining feature: the ability to fire multiple bullets with a single trigger pull.

For that reason and the fact that these guns are used for hunting and home defense, firearm specialists typically don’t call them “assault weapons” but describe them as:

- “modern sporting rifles,”

- by their make/model (like “AR-15”), or

- with functional descriptors like “semi-automatic rifle.”

Nevertheless, the politicians who sponsored the 1994 law labeled these semi-automatic guns “assault weapons.” This term sounds very similar to “assault rifles,” which happen to be the most common firearms used by soldiers and terrorists.

The lawmakers’ decision to use those easily confused terms accords with a 1988 booklet written by Josh Sugarmann, the founder of a prominent gun control organization called the Violence Policy Center. In it, he wrote about the “new topic” of “assault weapons” and laid out this strategy for banning them:

The weapons’ menacing looks, coupled with the public’s confusion over fully automatic machine guns versus semi-automatic assault weapons—anything that looks like a machine gun is assumed to be a machine gun—can only increase the chance of public support for restrictions on these weapons.

Many journalists have advanced this agenda by using the term “assault weapons” to describe a broad range of semi-automatic guns. These include the most commonly sold rifles in America, more than 19.8 million of which are now in circulation.

Numerous journalists and politicians have also conflated “assault weapons” with “assault rifles” by applying both of these terms to semi-automatic guns. This is chronicled in the nation’s leading authority on journalism lingo, the Associated Press Stylebook. A decade ago, the 2011 Stylebook distinguished between “assault weapons” and “assault rifles” as follows:

assault weapon: A semi-automatic firearm similar in appearance to a fully automatic firearm or military weapon. Not synonymous with assault rifle, which can be used in fully automatic mode.

This splitting of verbal hairs between semi-automatic “assault weapons” and military “assault rifles” led journalists to misuse these terms, but instead of fixing this confusion, the 2015 Stylebook made it worse. It did this by combining both terms into a single definition while stating that they “are often used interchangeably,” but “some” journalists “make the distinction that assault rifle is a military weapon….”

The use of similar and even identical terms to describe materially different weapons violates a basic principle of honest reporting stressed in journalism guidebooks: “use jargon only when necessary and define it carefully.”

Like the 1986 ban on automatic weapons, the 1994 ban on semi-automatic “assault weapons” had an exception for guns legally owned prior to the law’s enactment. Unlike the 1986 ban, however, the 1994 ban was not permanent. That’s because lawmakers included a provision that sunset the ban in 10 years as a compromise to secure enough votes to pass it and to provide time to “investigate and study” its “impact, if any, on violent and drug trafficking crime.”

The law required the U.S. Attorney General to conduct and publish such a study within 30 months of the ban’s enactment, and the study concluded that “the public safety benefits of the 1994 ban have not yet been demonstrated.” A similar study funded by the U.S. Department of Justice was published in 2004, the year the law was due to expire. It found that the ban had:

no discernible reduction in the lethality and injuriousness of gun violence, based on indicators like the percentage of gun crimes resulting in death or the share of gunfire incidents resulting in injury, as we might have expected had the ban reduced crimes with both AWs [assault weapons] and LCMs [large-capacity magazines].

On the other hand, the authors of the study noted that the effects of the law “are still unfolding and may not be fully felt for several years into the future,” and so it is “premature to make definitive assessments of the ban’s impact on gun violence.”

When the ban expired in 2004, various members of Congress sponsored bills to renew it, but none of them passed.

“High Capacity” Magazines Were Banned From 1994–2004

The same 1994 law which banned many semi-automatic guns until 2004 also banned “large capacity ammunition feeding devices” for the same period. The most common of these devices are detachable magazines (or “mags” for short), which hold and feed ammunition into the vast bulk of semi-automatic guns.

The politicians who wrote the law applied the term “high capacity” to mags that hold more than 10 rounds, even though these are standard on many popular handguns and rifles. For example, the stock magazine for a Glock 19, one of the best-selling handguns in the world, holds 15 rounds.

In fact, mags that hold more than 10 rounds are so common that more than 150 million of them are currently in circulation in the United States.

As a general rule, mags with more capacity are a tactical advantage because they allow the shooter to fire more bullets without reloading. However, a trained gunman can swap out a mag in one second. This allows mass shooters to effectively bypass the capacity restriction by bringing multiple mags to an attack. In contrast, it is not practical for the many millions of citizens who legally carry concealed firearms to keep a stockpile of mags on their waist.

Another tradeoff on mag size is that larger ones are bulkier, which can make weapons less concealable and harder to maneuver. Also, very large mags tend to jam, like the 100-round magazine used by the perpetrator of the 2012 “Dark Knight” movie theater massacre in Aurora, Colorado.

What Happened in the Wake of the 1994 Law?

The 1994–2004 ban on certain semi-automatic guns and 10+ round mags correlates with a slight decline in the portion of the U.S. population killed in mass shootings, but the association is weak, and there is no clear pattern:

Furthermore, the ban did not begin until the last 3.5 months of 1994, and:

- production of these weapons in 1994 was more than twice that of a typical year because people rushed to buy them before the ban took effect.

- a 2002 paper in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology found that the rush to buy these guns “produced the unintended consequence of making AWs more accessible” through at least mid-1996.

- the portion of people killed in mass shootings was lower in 1996 than in six of the eight years that followed while the ban was in effect.

Most importantly, Biden’s statement suffers from the sophomoric myth that association proves causation. Students are taught to avoid this fallacy in high school, but reporters, commentators, and even scholars often embrace it. In the words of an academic textbook about analyzing data:

Association is not the same as causation. This issue is a persistent problem in empirical analysis in the social sciences. Often the investigator will plot two variables and use the tight relationship obtained to draw absolutely ridiculous or completely erroneous conclusions. Because we so often confuse association and causation, it is extremely easy to be convinced that a tight relationship between two variables means that one is causing the other. This is simply not true.

The reason why this is not true is because many other factors can affect events like mass shootings, and there is frequently no objective way to isolate and quantify the effects of a single factor. With regard to the 1994 ban, just a few of the many factors that could have been at play during this era include the following:

- The very same 1994 law that enacted the firearm and magazine restrictions also contained a massive array of measures to reduce violent crime, including incentives for states to increase “the percentage of convicted violent offenders sentenced to prison” and increase “the average prison time which will be served in prison by convicted violent offenders.” This is significant because the vast bulk of murders are committed by people with long rap sheets.

- Wall-to-wall media coverage of mass shootings—which began with the Columbine school massacre of 1999—has since motivated many copycat killers seeking fame. Notably, the infamous Columbine mass murder occurred in the midst of the 1994–2004 ban.

- Less than 1% of all murders in the U.S. occur in mass shootings, and the overall murder rate fell by 39% during the years of the ban. Thus, the slight decline in mass shootings may be a consequence of the much larger decline in all murders. This is why the 2004 DOJ-funded study concluded that “we cannot clearly credit the ban with any of the nation’s recent drop in gun violence.”

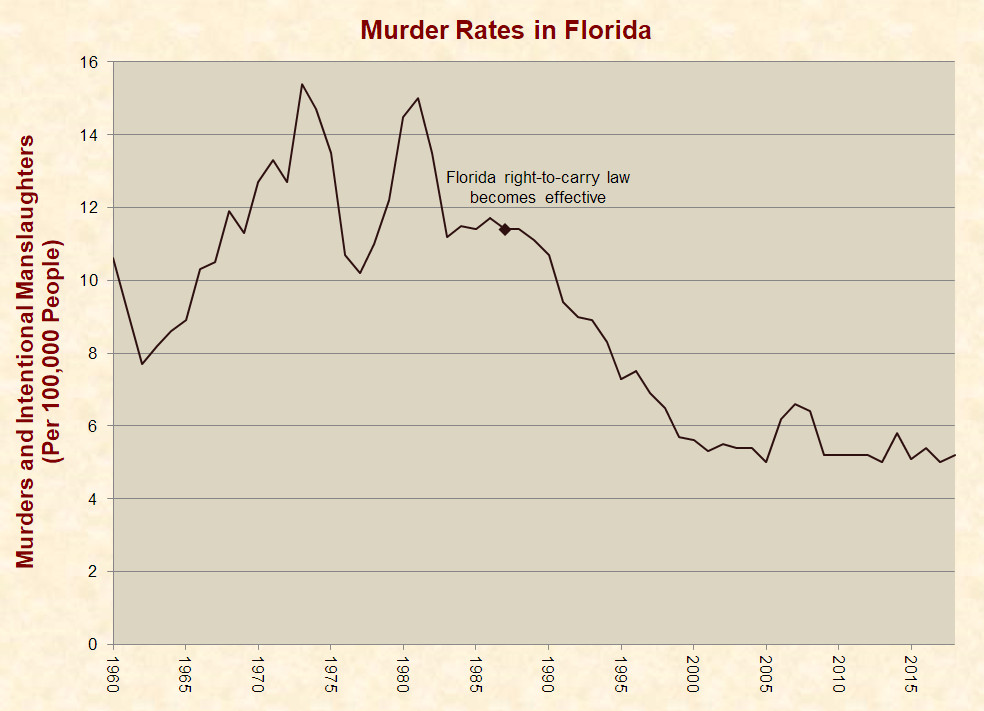

Using the childish logic of Biden, one would be forced to conclude that the right-to-carry law enacted by Florida in 1987 is responsible for the massive drop in murder rates that occurred in its wake:

The chart above shows what a strong association looks like, but even still, one cannot draw definitive conclusions from it because a multitude of other factors could be at play.

Biden’s & PolitiFact’s Phony Data

As proven by the data above, Biden’s claim that “mass shootings tripled” after the 1994–2004 ban has no basis in reality. However, a PolitiFact article by Jon Greenberg alleges it is “mostly true.”

PolitiFact attempts to support this claim by citing a paper published in 2019 by the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. The details of this study are hidden behind a $60 paywall, but there, the authors reveal that their count of mass shootings is “restricted to incidents reported by all three” of the following sources: “Mother Jones Magazine, the Los Angeles Times and Stanford University.”

Using that methodology—which relies on the absurd notion that all three of their sources have complete data stretching back for decades—the study presents the following chart that shows zero mass shooting deaths in 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2002, and 2004:

In other words, the paper ignores numerous people killed in mass shootings during the period of the ban, pretending as if these events and many others never took place:

- The 1995 Corpus Christi, TX workplace shooting, where a gunman murdered five people.

- The 1996 Fort Lauderdale, FL workplace shooting, where a gunman murdered five of his former coworkers.

- The 1997 Orange, CA workplace shooting, where a gunman murdered four people.

- The 2001 Melrose Park, IL workplace shooting, where a gunman murdered four people.

- The 2002 Rutledge, AL farm shooting, where a gunman murdered six members of his girlfriend’s family.

Further illustrating the inanity of this study, Dr. Louis Klarevas of Columbia University, a Ph.D. who specializes in mass-casualty violence, skewered the paper for having “a large number of misclassifications.”

Yet, PolitiFact treats this deceitful data as if it were fact, and healthcare professionals are invited to be brainwashed by it because the paper is “Accredited for Continuing Medical Education.”

– – –

James D. Agresti is the president of Just Facts, a think tank dedicated to publishing rigorously documented facts about public policy issues.

It’s crucial to differentiate between fully automatic firearms, which have been banned since 1986, and semi-automatic rifles that were restricted under the 1994–2004 ban. The data suggesting limited impact on reducing gun violence highlights how the effectiveness of such bans remains debatable.

It almost looks like those bans create a short-term decrease, but over next few years amount of incidents rise higher than even pre-ban numbers.