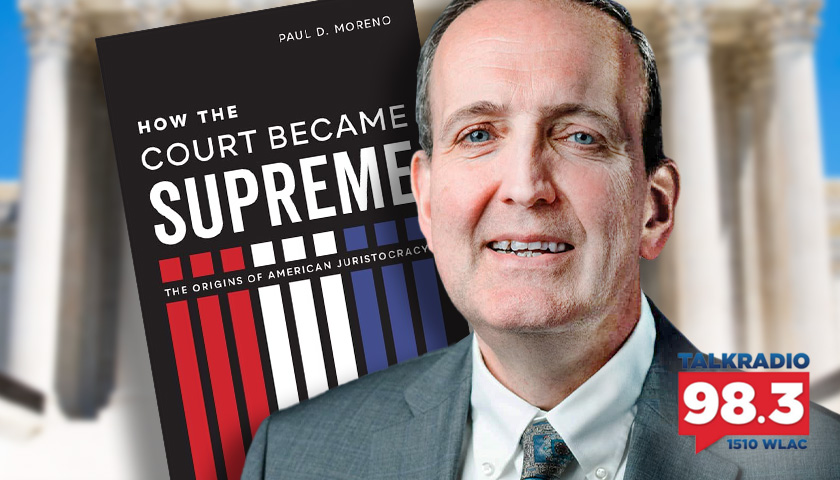

Live from Music Row, Monday morning on The Tennessee Star Report with Michael Patrick Leahy – broadcast on Nashville’s Talk Radio 98.3 and 1510 WLAC weekdays from 5:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. – host Leahy welcomed Hillsdale professor of history and author of the new book How the Court Became Supreme to the newsmaker line to discuss his book, including important instances that have contributed to the undue centralization of the American constitutional system.

Leahy: We welcome to our newsmaker line right now, Professor Paul Moreno. He’s a professor of history at Hillsdale and the dean of social sciences. He has a new book, How the Court Became Supreme: The Origins of American Juristocracy. Professor Moreno, thanks so much for joining us today.

Moreno: Thank you for having me.

Leahy: What’s your complaint against the judiciary? By the way, I’m going to join you in the complaint, but what’s your complaint?

Moreno: (Chuckles) Mostly that it’s not playing its proper role in the constitutional system. Instead of being supreme over the judicial branch as the Founders intended it, it’s become supreme over the states, over the Congress, and over the executive.

So they more or less turn themselves into the sovereign. And in 1958, they made a claim that the Constitution says that the Constitution laws are made in pursuance thereof, and treaties are the supreme law of the land. And in 1958 the Court said our decisions are also the supreme law of the land. So that’s a reality.

Leahy: You know, I’m kind of a buff of the Constitution. We’ve got a little competition for high school kids, the National Constitution Bee, which we’ve done for six years.

And we give away scholarships to the top students in the country who study a little book that we wrote called The Guide to the Constitution and Bill of Rights for Secondary School Students. I was not familiar with that 1958 decision. Tell us a little bit about that.

Moreno: It was in the aftermath of Brown versus Board of Education. The Court said that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. And that’s really what gave the Court the kind of sort of moral legitimacy that it’s had ever since then, that they did the right thing about race relations in America.

And that particular case, Cooper against Aaron, came out of the attempt to desegregate the Little Rock, Arkansas high school, a very famous incident where Eisenhower had to send in the National Guard. And it was a very sort of dramatic moment in the history of the civil rights movement.

And so people didn’t notice what the Court said about itself in that decision because it was sort of overshadowed by the drama, sort of the righteous drama of the desegregation movement.

Leahy: But I guess it’s a precedent now that the Court has followed for what, 50, 60-odd years now, right?

Moreno: Yes. That’s one of the problems is, until the last term of the Supreme Court, where obviously liberals are very upset now that you have a clear conservative majority on the Court, that the American people more or less came to accept that the Constitution is what the Court says it is.

Leahy: Are there ways to push back against this judicial primacy that we’re seeing these days?

Moreno: Absolutely. The first thing that liberals started talking about was old-fashioned court-packing and expanding the size of the Court. That’s been done before. FDR proposed to do that in the 1930s, and it really destroyed his presidency.

But there are a lot of other ways in which you can control the Court. If you read Article Three, Section Two of the Constitution, congress can change the Court’s jurisdiction, especially the kinds of cases that the Supreme Court can hear on an appeal.

So there are – and then, of course, the removal of judges by impeachment. That’s only been tried once back in 1805, and it failed. So there are a lot of rules …

Leahy: But the removal for impeachment must be for a cause. Must be for a cause. It can’t be we don’t like your decision.

Moreno: Because it happens so infrequently and it’s a good thing that happens so infrequently. Yes, most people do accept the view that impeachment has to be for crimes, something that you’d be indictable for outside of sort of just a political setting.

But there have always been people who argued that, no, it could be for policy reasons. There were some Jeffersonian Republicans who called for exactly that …

Leahy: Do you see that in the Constitution? I don’t see that in the Constitution.

Moreno: But the language says treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

Leahy: But a decision itself isn’t a high crime or misdemeanor, even if you disagree with it. Right?

Moreno: Yes. If you interpret crimes and misdemeanors as being like treason, bribery, or theft, or ordinary crimes. Gerald Ford when he was in the House of Representatives, and he was leading an effort to impeach Justice William O. Douglas, who hadn’t done anything, probably not anything in ordinary criminal terms, but Ford said impeachable offense is whatever the majority of the House Representatives says it is.

I think you’ve seen that in the presidential context with Trump’s impeachments as well. So you’re right, it’s a minority view, but there’s always been that alternative. But Article Three says that the judges will hold their offices during good behavior.

So there’s an argument that good behavior means something short of impeachable, that impeachment is yet for criminal cases, but good behavior could mean, again, not behaving in an appropriately judicial way, usurping legislative function.

Leahy: Crom Carmichael is in the studio and he has a question for you.

Carmichael: I’m going to agree with the professor here, because before a judge takes office, they take an oath of office to uphold the Constitution. If they abuse the Constitution, then that could be considered an impeachable offense, and the people who are considering it are the ones who determine whether it is or not.

Leahy: And so that’s back to your argument, the Gerald Ford argument, Professor Moreno?

Moreno: Yes, and as a practical matter, again, because impeachment happens so infrequently, every time it comes up we’re almost starting from scratch, and this question of what is an impeachable offense arises anew.

To Bill Clinton, technically, the charges were sort of perjury, but most people knew that it was really about his disgraceful behavior, sort of unbecoming of the office of the president.

Leahy: Is there a role for state attorney general here?

Moreno: That’s a very interesting question, because the Court’s power has also come about with changes in the American legal system and American legal education that are really important.

And the fact that many states have elected attorneys general who are separate from the governors, that’s really, I think, a very dysfunctional system. I think that the federal system where the attorney general is under the control of a unitary executive is much preferable.

So here you have rogue attorney generals who are going off sort of pursuing their own political agendas rather than enforcing the law.

Leahy: But aren’t those attorneys general representing the states in the federalist system?

Moreno: Yes, but usually very often the ways that the states have been complicit in undermining the federal system is another part of the story. The Supreme Court back in the 19th century, most of what the Court did, especially under John Marshall, was sort of defend the federal system and maintain the balance between the federal government and the states.

But the states have largely been subordinated to the federal government, mostly by offering money with strings attached through the federal – the so-called federal – spending power. So states themselves have contributed to the undue centralization of the American constitutional system.

Listen to today’s show highlights, including this interview:

– – –

Tune in weekdays from 5:00 – 8:00 a.m. to The Tennessee Star Report with Michael Patrick Leahy on Talk Radio 98.3 FM WLAC 1510. Listen online at iHeart Radio.

Photo “Paul Moreno” by Hillsdale College. Background “United States Supreme Court” by Senate Democrats. CC BY 2.0.